SANDRA BLAND: #SayHerName Loud or Not at All

It is customary that whenever I go to my Nana’s house I turn the car speakers as low as possible. She has super hearing. Sometimes I forget, and the following conversation takes place:

“What’s up Nana Boo?”

“I heard you before you got the house, girl. I told you about playing your music too loud.”

“It wasn’t too loud.”

“I heard you before I saw you.”

“Yes ma’am. I’m sorry.”

“Don’t bring attention to yourself.”

Don’t bring attention to yourself.

Physically this is impossible. I am a black woman over six feet tall. My laugh sounds like an exploding mouse. I squeak loudly and speak quickly when I get excited. I like knock in my trunk and bass in my music. Don’t bring attention to yourself. I frequently heard this warning as a girl and well into my adult life. I rarely take it as a slight on my grandmother’s account – though she is the master of throwing parasol shade. She spoke to me with a quiet urgency in her warning. In the wake of the murders of Jordan Davis, Sandra Bland, and other black lives that vigilantes and mainstream media deemed irrelevant, I understand her warning better from the perspective of sound.

As a loud, squeaky black woman I am especially attuned to how my sonic footprint plays into how I live and if I should die. As a black woman, the bulk of my threat is associated with my loudness. My blackness sonically and culturally codes me as threatening due to the volume of my voice. This is amplified, as a southern black woman. I exist and dare to thrive in a country that historically and socially tries to deflate my agency and urgency. The clarity of my sentiments, the establishment of my frustration, and the worth of my social and cultural interventions are connected to how others hear my voice. It is not what I say but how I say it.

Black women navigate multiple codes of sonic respectability on a daily basis. Their sonic presence is seldom recognized as acceptable by society. Classrooms, homesites, corporate spaces, kitchen tables, and social media require a different tone and volume level in order to gain access and establish one’s credibility. Like other facets of their existence, the way(s) black women are expected to sound in public and private spaces is blurry. What connects these spaces together is a patriarchal and racially condescending paradigm of black women’s believed inferiority. A black women’s successful assimilation into American society is grounded in her ability to master varying degrees of quiet and silence. For black women, any type of disruptive pushback against cultural norms is largely sonic in nature. A grunt, shout, sigh, or sucking teeth instigates some type of resistance. Toning these sonic forms of pushback—basically, silencing themselves—is seen as the way to assimilate into mainstream American society.

In what follows I look at the tape of Sandra Bland’s arrest from this past summer to consider what happens when black women speak up and speak out, when they dare to be heard. As the #SayherName movement attests, black women cannot express sonically major and minor touchstones of black womanhood – joy, pleasure, anger, grief – without being deemed threatening. These sonic expressions force awareness of the complexity of black women’s experiences. In the case of Sandra Bland, I posit that the video of her arrest is not a video of her disrespecting authority but rather shows her sonic response to officer Brian Encinia’s inferred authority as a police officer. I read her loud and open interrogation of Encinia’s actions as an example of what I deem sonic disrespectability: the use of sound and volume to contest oppression in the shape of dictating how black women should or should not act.

The sonic altercation in the video (see full-length version here) sets the stage for Encinia’s physical reprimand of Bland, a college graduate from Prairie View A&M who hailed from Chicago. Bland is not physically threatening—i.e. she emphatically states she’s wearing a maxi dress—but her escalating voice startles and even intimidates Encinia. Bland is angry and frustrated at Encinia’s refusal and to answer her questions about why she was pulled over. Encinia’s responses to Bland’s sonic hostility are telling of his inability to recognize and cope with her anger. In fact, he refuses to answer her questions, and she repeats them over and over again while he barks orders. Encinia states later in the dashboard camera that Bland kicks him and thus forces him to physically restrain her. However, Bland’s vocal assertion of her agency is more jarring than her physical response to Encinia’s misuse of power.

The dashboard camera footage is indicative of their vocal sparring match. Encinia’s voice starts calm and even. He explains to Bland he pulled her over for failure to indicate a lane change. Bland’s responses are initially low and nearly inaudible. However, after Encinia asks Bland if she is “okay,” her responses are much louder. She does not just follow orders but expresses her displeasure in sonic ways, while she stays in the car. His tone shifts when Bland refuses to extinguish her cigarette. Encinia then threatens to pull her out of the car for disobedience. He begins to yell at her. Bland then voices her pleasure in taking Encinia and his complaint to court. “Let’s take this to court. . .I can’t wait! Ooooh I can’t wait!” Bland’s pleasure in taking Encinia to court is an expression of her belief in her own agency. The act of voicing that pleasure is particularly striking because it challenges an understanding of courts and the justice system as hyperwhite and incapable of recognizing her need for justice. Her voice is clear, loud, and recognizably angry.

Her voice crescendos throughout the video, signifying her growing anxiety, tension at the situation, and anger for being under arrest. However, Bland’s voice begins to crack. Her sighs and grunts signify upon her disapproval of Encinia’s treatment of her physical body and rights. Once handcuffed, Bland’s voice is very high-pitched and pained, a sonic signifier of submission and Encinia’s re-affirmation of authority. She then is quiet and a conversation between Encinia and another officer is heard across the footage.

Many critiques of Bland center around her ‘distasteful’ use of language. One critic in particular described the altercation as “an African American woman had too much mouth with the wrong person and at the wrong time.” The assumption in those critiques is that she was not properly angry. Instead of a blind obedience of Enicnia’s inferred authority (read: superiority), she questions him and his inability to justify his actions. Sandra Bland’s sonic dis-respectability (dare I say, ratchet), is a direct pushback against the cultural and social norms of not only rural Southern society but the mainstream American (inferred) belief of southern black folks’ blind respectability of white authority and law enforcement.

Although Bland was a graduate of a southern HBCU, I do not want to assume that Bland possessed the social sensibilities that upheld this unstated social practice of blindly obeying white authority. Her death runs parallel to those of Emmett Till and Mary Turner. The circumstances of Till’s death swirled around his alleged whistling at a white woman – read as a sonic signifier of Till’s black masculine sexuality instead of boyhood – and disregard for white femininity, a protected asset of white men’s authority. Till, from Illinois like Bland, allegedly ignored his cousins’ warnings about the ‘proper protocol’ of interacting with white folks. Mary Turner, a black woman from Valdosta, Georgia, spoke out publicly against the lynching of her husband in 1918. She and her unborn child were also lynched in response to her sonic audacity. Before her death, members of the mob cut open her belly and her unborn baby fell on the ground; it was stomped to death after it gave out a cry. Turner’s voice disrupted white supremacy. Her baby’s lone cry re-emphasized it. Sound grounds much of the racial and gendered violence in the South.

The Southern U.S. emphasizes listening practices as part of social norms and cultural traditions. Listening was an act of survival more so than vocalizing the challenges facing black folks. (Jennifer Stoever’s upcoming book on the sonic color line addresses how advertisements for runaway slaves, for example, mentioned whether they were good listeners, as a way to codify whether they were compliant slaves.). Consider my grandmother’s warning about not bringing attention to myself. In her eyes, by not bringing attention to myself I’m able to remain invisible enough to successfully navigate society’s expectations of my blackness and my womanhood. Silence and listening are tools of survival. Contrarily, Bland’s loud disapproval and emphatic use of curse words registered her blackness and womanhood as threatening. She was coded as less feminine and therefore threatening because of her direct verbal confrontation with Encinia. She was not quiet or polite, especially in the south where quiet is the ultimate and sole form of women’s politeness and respectability. The combination of these multiple representations of black women’s anger invoked Encinia’s hyper-authoritative response to regain control of the situation.

Black folks are increasingly pushing back against “being in their place.” Sandra Bland’s death is rooted in an unnecessarily escalated fear of black women literally speaking their truth to power. In a moment where black women are speaking on multiple wavelengths and levels of volume, it is imperative to single out instances and then implode outdated cultural and social practices of listening.

—

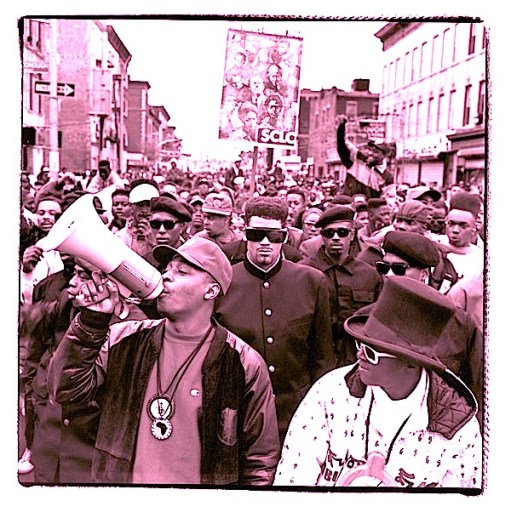

Featured image:”Sandra Bland is Her Name” by Flickr user Light Brigading, CC BY-NC 2.0

—

Regina Bradley is a writer, scholar, and researcher of African American Life and Culture. She is a recipient of the Nasir Jones HipHop Fellowship at Harvard University (Spring 2016) and an Assistant Professor of African American Literature at Armstrong State University. Dr. Bradley’s expertise and research interests include hip hop culture, race and the contemporary U.S. South, and sound studies. Dr. Bradley’s current book project, Chronicling Stankonia: Recognizing America’s Hip Hop South (under contract, UNC Press), explores how hip hop (with emphasis on the southern hip hop duo Outkast) and popular culture update conversations about the American South to include the post-Civil Rights era. Also known as Red Clay Scholar, a nod to her Georgia upbringing, Regina maintains a critically acclaimed blog and personal website – http://www.redclayscholar.com. She is a regular writer for Sounding Out!

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

I Been On: BaddieBey and Beyoncé’s Sonic Masculinity — Regina Bradley

“President Obama: All Over But the Shouting?” — Jennifer Stoever

Óyeme Voz: U.S. Latin@ & Immigrant Communities Re-Sound Citizenship and Belonging-Nancy Morales

Afrofuturism, Public Enemy, and Fear of a Black Planet at 25

Twenty-five years after Do the Right Thing was nominated but overlooked for Best Picture, Spike Lee is about to receive an Academy Award. At the beginning of that modern classic, Rosie Perez danced into our collective imaginations to the sounds of Public Enemy. Branford Marsalis’s saxophone squealing, bass guitar revving up, she sprung into action in front of a row of Bed-Stuy brownstones. Voices stutter to life: “Get—get—get—get down,” says one singer, before another entreats, “Come on and get down,” punctuated by James Brown’s grunt, letting us know we’re in for some hard work. In unison, Chuck D and Flavor Flav place us in time: “Nineteen eighty-nine! The number, another summer…” The track’s structure, barely held in place by the guitar riff and a snare, accommodates Marsalis’s saxophone playing continuously during the chorus, but intermittent scratches and split-second samples make up the plurality of the sounds. The two rappers’ words take back the foreground in each verse, and their cooperative and repetitive style reinforces the song’s message during the chorus, when they trade calls and responses of “Fight the power!”

.

Throughout the credits, lyrics and musical elements are shot through with noise: machine guns, helicopters, jet engines—even the sax, the only conventional instrument at work, seems to cede ground to these disruptions. The dancing form of Perez, unlike the other figures taking part in the performance, is silent but visible; she’s the only one who seems fully in control of the relationship between her body and the sounds. Perez’s performance of “Fight the Power” is an antidote to fantasies of masculine technological mastery: her movements, while sometimes syncopated, are discrete to the point of appearing martial—the steps are improvised but the skills are practiced; she’s ready to step into the ring.

Fulfilling Spike Lee’s request to Public Enemy to provide a theme for the movie, “Fight the Power,” made it onto the group’s iconic album Fear of a Black Planet the following year. In Anthem, Shana Redmond names the song “perhaps the last Black anthem of the twentieth century,” noting that it bridges divides like the space between America’s East and West Coasts (261-262). It does so as part of the film’s opening sequence through juxtapositions: the sound of helicopters, a signature of LAPD surveillance, crosses the New York City streetscape in stereo. On the album, however, a radically different opening sets the tone for the track. A speech by Thomas Todd taunts, “Yet our best trained, best equipped, best prepared, troops refuse to fight. Matter of fact, it’s safe to say that they would rather switch than fight.” The speaker draws out the breathy, sibilant ending of the word “switch” to create a double entendre; voiced this way, “they would rather switch” connotes both disloyalty in the “fight” and a swishy movement of the hips attributed to effeminate men. In later years, the crystal-clear sample would resurface across genres; it was the only lyrical component of DJ Frankie Bones’s “Refuse to Fight” in 1997, a track purely intended for dancing in the blissful atmosphere of the rave scene, which evacuated militancy to make room for “Peace, Love, Unity, and Respect.”

On PE’s album, the version of the song introduced by this sample strikes a stark contrast with its rendition in the film as the vehicle for an inexhaustible and defiant female dancer in a neighborhood wracked by disempowerment.

Identifying Fear of a Black Planet as “the first true rap concept album,” Tom Moon of the Philadelphia Inquirer recognizes the role of the DJ and production team in achieving its unique synthesis between melodic and meaning elements. At first he calls the sample-heavy stage for the rap performance “a bed of raw noise not unlike radio static,” but he later parses out how this “noise” actually consists of a rich informational emulsion:

an environment that can include snippets of speeches, talk shows, arguments, chanting, background harmonies, cowbells and other percussion, drum machine, treble-heavy solo guitar, jazz trumpet, and any number of recorded samples.

The underlying concept driving the album is the ominous encounter between Blackness and whiteness, which has become an object of fear and fascination throughout centuries of American culture. As the role of their anthem in the film about a neighborhood undergoing violent transformation indicates, the meeting of Black and white is not a fearsome future to come, but a present giving way to both reactionary and revolutionary possibilities. And it goes a little something like this.

In this post, I provide track-by-track sonic analysis to show how, over the past 25 years, Fear of a Black Planet has contributed to Afrofuturism through its invocation of prophetic speech and through its place on the cultural landscape as a touchstone for the beginning of the 1990s. As the first song, “Contract on the World Love Jam,” insists, in one of the “‘forty-five to fifty voices’” Chuck D recalls sampling for this track alone, “If you don’t know your past, then you don’t know your future.”

This moment continues to resonate in the present as a repository of ideas and modes of expression we still need. Along with the hypnotic efficacy of rhetoric like “Laser, anesthesia, ‘maze ya/ Ways to blaze your brain and train ya,” and Flavor Flav’s subversive humor, I argue that Fear of A Black Planet engages with Afrofuturism by using sound to instigate the kind of “disjuncture” that Arjun Apparurai called characteristic of culture under late modern global capitalism. This kind of practice thematizes Fear of a Black Planet: it uses sound to confront the boundaries of information, desire, and power on decisively African Americanist terms. PE cut through the noise with a new sound, one that still resonates 25 years later.

Sampling is an indispensable strategy on Fear of a Black Planet. Yet as Tricia Rose contends, the sound of hip-hop arises out of a systematic way of moving through the world rather than as a “by-product” of factors of production. In Capturing Sound, Mark Katz identifies Public Enemy’s sampling with “the predigital, prephonographic practice of signifying that arose in the African American community” (164). Scholars and music critics alike have dubbed this era the “golden age” of digital sampling, a moment when new technology made it possible for musical composition to rely on audio appropriated from a panoply of sources but before the financial and methodological obstacles of copyright clearance emerged in force. As Kembrew McLeod and Peter Di Cola argue in Creative License, challenges imposed by the cost of licensing fees now associated with sampling make contemporary critics doubtful that Black Planet could be produced today (14). In retrospect, the album shows us how the “financescape” of popular music has evolved out of sync with the technoscape: by placing property rights in the way of the further development of the tradition inaugurated by the Bomb Squad (PE DJs Terminator X, Hank Shocklee, Keith Shocklee, and Eric “Vietnam” Sadler).

In 2011, when asked by NPR’s Ira Flatow about sampling as an art form, Hank Shocklee pointed out that, “as we start to move more toward into the future and technology starts to increase, these things have to metamorphosize, have to change,” further insisting that this means, “everything should be fair use, except for taking the entire record and mass producing it and selling it yourself.” Realizing how sampling entails not just the use of sound but its transformation, he stakes out a radical position on intellectual property, noting that the law tends to protect record companies rather than performers:

Stubblefield, [the drummer], is not a copyright owner. James Brown is not a copyright owner. George Clinton is not a copyright owner. The copyright owners are corporations… when we talk about artists, you know, that term is being used, but that’s not really the case here. We’re really talking about corporations.

Driven by such a skeptical orientation to the notion of sound as property, Fear of a Black Planet is both unapologetic and unforgiving in its sonic promiscuity. It weds a dizzying repertoire of references from the past to a sharp political critique of the present, embodying the role of hip-hop in transforming the relationship between sound and knowledge through whatever means the moment makes available.

A different Spike Lee joint (Jungle Fever, 1991, with a soundtrack by Stevie Wonder) enacts the spectacle behind the title track on Fear of a Black Planet. Interracial sexuality, as one of many dimensions of living together across the color line, is the most explicit “fear” a Black Planet has in store, but two tracks undercut the flawed notions of white purity at the heart of the issue.

Chuck D dismisses the concerns of an imaginary white man at the start of each verse: “your daughter? No she’s not my type… I don’t need your sister… man, I don’t want your wife!” He subsequently shifts focus to the questions of “what is pure? who is pure?” what would be “wrong with some color in your family tree?” and finally, whether it might be desirable for future generations to become more Black, owing to the adaptive value of “skins protected against the ozone layers/ breakdown.” Chuck’s line of questioning assuages the anxiety that the imagined white interlocutor might feel in order to address more fundamental planetary concerns, like environmental degradation. In addition to staging a conversation in which a Black man enjoins a white man to listen to reason, the structure of the track involves Flavor Flav in a parallel dialogue. Flav replies to each of Chuck’s initial reassurances the same playful counterpoint: “but suppose she says she loves me?” He keeps posing the hypothetical in one verse after another, despite Chuck D’s repeated insistences that he isn’t interested in white women, suggesting that “love,” an irrational but undeniably powerful motivation for interracial encounter, is just as compelling as a putatively rational browning of the planet’s people. “Pollywannacracka” riffs on the same subject with hauntingly distorted vocals and a chorus that includes a mocking crowd calling the Black woman or man who desires a “cracka” out their name (the drawn out refrain is the word “Polly…”) and a teasing whistle. These derisions reduce the taboo topic of interracial liaisons to the stuff of schoolyard taunts while playing out tense confrontations among Black men and Black women in between the verses.

Black Planet also presented PE the first opportunity to reconstruct their reputation after former manager, Professor Griff, made anti-Semitic comments–“Jews control the media”—in an interview. PE takes the public’s temperature on “Incident at 66.6 FM,” which reiterates snippets from listeners calling in to radio broadcasts; most of the callers represented excoriate the group but a few defend them, including erstwhile DJ Terminator X, who shouts himself out.

This inward-facing archive acquires more material on the album’s most self-referential track, “Welcome to the Terrordome.” The song elliptically places the scrutiny the group has faced in perspective through allusions that are rendered even more involuted through repetition and internal rhyme: “Every brother ain’t a brother… Crucifixion ain’t no fiction… the shooting of Huey Newton/from the hand of a nig that pulled the trig.” The brother who allegedly ain’t one was David Mills, the music journalist who publicized Griff’s comments.

Noting Chuck’s rather transparent analogy between this betrayal and the myth that the Jewish community was responsible for killing Jesus, Robert Christgau, in Grown Up All Wrong, concludes that “the hard question isn’t whether ‘Terrodome’ is anti-Semitic—it’s whether that’s the end of the story” (270-271). It isn’t. “War at 33 1/3” redraws these same lines by advising that “any other rapper who’s a brother/Tries to speak to one another/Gets smothered by the other kind,” hearkening back to the earlier song’s assertion not all skinfolk are kinfolk. The song samples speech from Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan that frames the titular “war” as a rhetorical contest.

The most collaborative jam on the album, co-written by Rage Against the Machine’s Zack De La Rocha, “Burn Hollywood Burn” enacts an acerbic critique of media representations of Blackness against the most party-perfect hooks on the album, including a sampled crowd repeating the three words of the refrain like a protest chant, a timeline provided by a pea whistle, and a horn sample looped for the gods.

Sustaining a militant ideal of Black masculinity in defiance of Hollywood’s Stepin’ Fetchit and Driving Miss Daisy scripts (both referenced by name), featured MCs Ice Cube and Big Daddy Kane occupy the track’s. Their forward-leaning posture demands they be taken seriously, like Chuck D, rather than coming off as whimsical and indulgent like Flavor Flav. Yet PE’s sound would be unrecognizable without Flav’s flavor to carry out the call-and-response structure of their performances. Flav voices a skit on the final verse of “Burn Hollywood Burn” in which he is invited to portray a “controversial Negro” as an actor; he asks if the role calls on him to identify with Huey P. Newton or H. Rap Brown, but to his chagrin, the invitation calls for “a servant character that chuckles a little bit and sings.” Contemporary audiences might associate Flavor Flav with the latter based on his reality TV persona, but the comic wit he brings to PE knowingly undermines strident posturing and demands that the audience listen more closely.

“Flavor Flav of Public Enemy at Way Out West 2013 in Gothenburg, Sweden” by Wikimedia user Kim Metso, CC BY-SA 3.0

Despite the comparatively trivial content of his lyrical presence on most tracks, Flav enhances the repertoire of knowledge at work across Fear of a Black Planet, deepening its cultural frame of reference and accentuating different elements of its sonic structure. On “Who Stole the Soul,” for example, after Chuck says, “Banned from many arenas/ Word from the Motherland/ Has anybody seen her,” Flav repeats after him, “Have you seen her,” emphasizing the allusion to ”Have You Seen Her?” by the Chi-Lites. Then, before Chuck has finished his next line, Flav repeats himself, stylizing the question “Have You Seen Her” with the same melody used by the Chi-Lites. Ingeniously, Flav modifies the allusion that Chuck makes in verbal form by using the timing and melodic structure of his repetition to produce a new timeframe within the existing track, doubling the ways in which this line alludes to a prior work.

On his own, Flav’s performances on Black Planet laugh through the pain of urban dystopia, the. concentrated poverty, premature death, and alienation from the amenities of citizenship he explores in “911 is a Joke” and “Can’t Do Nuttin’ For Ya Man.” “911” is especially notable for coupling Flav’s cynical appraisal of life and death in the hood to repetitive verse structures, a tight rhyme scheme consisting mostly of couplets, a chart-ready beat (the song reached #1 on the Billboard Hot Rap Singles list), and an unforgettable quatrain as the hook: “Get up, get, get, get down/911 is a joke in your town/ Get up, get, get, get get down/Late 911 wears the late crown.”

.

The notion of getting down to misery is disturbing, but that’s all you can do. The track ends with a particularly macabre sample: the laughter of Vincent Price, the same heard at the harrowing conclusion of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.” “Can’t Do Nuttin’ For Ya Man,” on the other hand, ends with Flav’s raspy laughter. While “911” ironizes the withdrawal of public resources from “your town” amid concentrated poverty, this song sends up the misfortunes urban denizens bring on themselves. The funky tune profanes the serious concerns of a man who’s fallen into a life of crime, offering no Chuck D-style self-help just “bass for your face.”

Mark Anthony Neal has called the generation that came of age in the 1990s the “Post-Soul” generation, and the many funk and soul references on Fear of a Black Planet, from the preceding sounds to the rallying cry of “Who Stole the Soul,” connect the first hip-hop of the 1990s to the prior generation of Black music. Repetition with difference allows the group to maintain a dialogue between their precedents in socially conscious popular music and the new intervention they intend to make. If “Fight the Power” signals the dawn of new era, so does the largely-forgotten “Reggie Jax,” the downtempo freestyle on which Chuck D coins the term “P-E-FUNK.”

Chuck’s neologism, which he introduces by spelling it out, “P-E-F-U-N and the K,” is a performative citation linking PE’s brand of hip-hop to the P-Funk of the 1970s: perhaps the defining expression of Afrofuturism in popular music. The morphology of “P-E FUNK” is highly novel, infixing a new element within an existing word and also facilitating the flow between the terms by enunciating their assonant sounds. This tactic for naming the fusion of hip-hop and P-Funk allows PE to continue a pattern initiated by their predecessor Afrika Bambaataa, whom they sample on “Fight the Power,” by inserting themselves into a particular artistic genealogy (traced by Ytasha Womack in Afrofuturism) animated by George Clinton, Bootsy Collins, and the mind-expanding antics of Parliament/Funkadelic.

Still from Public Enemy video for “Do You Wanna Go My Way?”

The intense polyrhythmic edifice of Fear of a Black Planet link past to (Afro)future, engaging in a radically heteroglossic practice of treating sound as information. Deploying the sound of knowledge and the knowledge of sound in the service of envisioning the world as it is, the album charts a dystopian itinerary for the 1990s that we need to comprehend how we arrived at the present. Rather than worrying that a Black Planet is something to fear, we might consider the lessons that emerged from past efforts to cope with developments already underway. If we listen to Flavor Flav and find that coping strategies are futile, at least we can party. And if we were right to call Chuck a prophet, then the dawn of the Black Planet he warned us about—characterized by neoliberal governance, gentrification, and boundaries that demand to be crossed—is a moment when the avant-garde tactics of Afrofuturism are becoming important to everyone. Citizens of Earth: Welcome to the Terrordome.

—

andré carrington, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor of African American Literature at Drexel University. His research on the cultural politics of race, gender, and genre in popular texts appears in journals and books including African and Black Diaspora, Politics and Culture, A Companion to the Harlem Renaissance, and The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Blackness In Comics and Sequential Art. He has also written for Callaloo, the Journal of the African Literature Association, and the Studio Museum in Harlem. His first book, Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction, is being published by University of Minnesota Press.

—

Featured Image: Still from “Fight the Power” video, color altered from b & w by SO!

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Straight Outta Compton… Via New York — Loren Kajikawa

Fear of a Black (In The) Suburb — Regina N. Bradley

They Do Not All Sound Alike: Sampling Kathleen Cleaver, Assata Shakur, and Angela Davis — Tara Betts

Recent Comments