Mr. and Mrs. Talking Machine: The Euphonia, the Phonograph, and the Gendering of Nineteenth Century Mechanical Speech

In the early 1870s a talking machine, contrived by the aptly-named Joseph Faber appeared before audiences in the United States. Dubbed the “euphonia” by its inventor, it did not merely record the spoken word and then reproduce it, but actually synthesized speech mechanically. It featured a fantastically complex pneumatic system in which air was pushed by a bellows through a replica of the human speech apparatus, which included a mouth cavity, tongue, palate, jaw and cheeks. To control the machine’s articulation, all of these components were hooked up to a keyboard with seventeen keys— sixteen for various phonemes and one to control the Euphonia’s artificial glottis. Interestingly, the machine’s handler had taken one more step in readying it for the stage, affixing to its front a mannequin. Its audiences in the 1870s found themselves in front of a machine disguised to look like a white European woman.

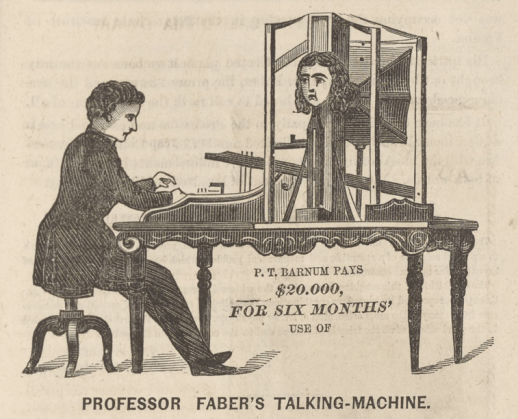

Unidentified image of Joseph Faber’s Euphonia, public domain. c. 1870

By the end of the decade, however, audiences in the United States and beyond crowded into auditoriums, churches and clubhouses to hear another kind of “talking machine” altogether. In late 1877 Thomas Edison announced his invention of the phonograph, a device capable of capturing the spoken words of subjects and then reproducing them at a later time. The next year the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company sent dozens of exhibitors out from their headquarters in New York to edify and amuse audiences with the new invention. Like Faber before them, the company and its exhibitors anthropomorphized their talking machines, and, while never giving their phonographs hair, clothing or faces, they did forge a remarkably concrete and unanimous understanding of “who” the phonograph was. It was “Mr. Phonograph.”

Why had the Euphonia become female and the phonograph male? In this post, I peel apart some of the entanglements of gender and speech that operated in the Faber Euphonia and the phonograph, paying particular attention to the technological and material circumstances of those entanglements. What I argue is that the materiality of these technologies must itself be taken into account in deciphering the gendered logics brought to bear on the problem of mechanical speech. Put another way, when Faber and Edison mechanically configured their talking machines, they also engineered their uses and their apparent relationships with users. By prescribing the types of relationships the machine would enact with users, they constructed its “ideal” gender in ways that also drew on and reinforced existing assumptions about race and class.

Of course, users could and did adapt talking machines to their own ends. They tinkered with its construction or simply disregarded manufacturers’ prescriptions. The physical design of talking machines as well as the weight of social-sanction threw up non-negligible obstacles to subversive tinkerers and imaginers.

Born in Freiburg, Germany around 1800, Joseph Faber worked as an astronomer at the Vienna Observatory until an infection damaged his eyesight. Forced to find other work, he settled on the unlikely occupation of “tinkerer” and sometime in the 1820s began his quest for perfected mechanical speech. The work was long and arduous, but by no later than 1843 Faber was exhibiting his talking machine on the continent. In 1844 he left Europe to exhibit it in the United States, but in 1846 headed back across the Atlantic for a run at London’s Egyptian Hall.

That Faber conceived of his invention in gendered terms from the outset is reflected in his name for it—“Euphonia”—a designation meaning “pleasant sounding” and whose Latin suffix conspicuously signals a female identity. Interestingly, however, the inventor had not originally designed the machine to look like a woman but, rather, as an exoticized male “Turk.”

“The Euphonia,” August 8, 1846, Illustrated London News, 96.

A writer for Chambers Edinburgh Journal characterized the mannequin’s original appearance in September of 1846:

The half figure of a man, the size known to artists as kit kat, dressed in Turkish costume, is seen resting, upon the side of a table, surrounded by crimson drapery, with its arms crossed upon its bosom. The body of the figure is dressed in blue merino, its head is surmounted by a Turkish cap, and the lower part of the face is covered with a dense flowing beard, which hangs down so as to conceal some portion of the mechanism contained in the throat.

What to make of Faber’s decision to present his machine as a “Turk?” One answer, though an unsatisfying one is “convention.” One of the most famous automata in history had been the chess-playing Turk constructed by Wolfgang von Kempelen in the eighteenth century. A close student of von Kempelen’s work on talking machines, Faber would almost certainly have been aware of the precedent. In presenting their machines as “Turks,” however, both Faber and Von Kempelen likely sought to harness particular racialized tropes to generate public interest in their machines. Mystery. Magic. Exoticism. Europeans had long attributed these qualities to the lands and peoples of the Near East and it so happened that these racist representations were also highly appealing qualities in a staged spectacle—particularly ones that purported to push the boundaries of science and engineering.

Mysteriousness, however, constituted only one part of a much larger complex of racialized ideas. As Edward Said famously argued in Orientalism Westerners have generally mobilized representations of “the East” in the service of a very specific political-cultural project of self- and other-definition—one in which the exoticized orient invariably absorbs the undesirable second half of a litany of binaries: civilization/barbarism, modernity/backwardness, humanitarianism/cruelty, rationality/irrationality. Salient for present purposes, however is the west’s self-understanding as masculine, in contradistinction to—in Said’s words—the East’s “feminine penetrability, its supine malleability.”

One possible reading of the Faber machine and its mannequin “Turk,” then, would position it as an ersatz woman. A depiction of the Euphonia and its creator, which appeared in the August 8, 1846 Illustrated London News would appear to lend credence to this reading. In it, the Turk, though bearded, features stereotypically “feminine” traits, including soft facial features, smooth complexion and full lips. Similarly, his billowing blouse and turban lend to the Turk a decidedly “un-masculine” air from the standpoint of Victorian sartorial norms. The effect is heightened by the stereotypically “male” depiction of Faber himself in the same illustration. He sits at the Euphonia’s controls, eyes cast down in rapt attention to his task. His brow is wrinkled and his cheeks appear to be covered in stubble. He appears in shirt and jacket—the uniform of the respectable middle-class white European man.

Importantly, the Euphonia’s speech acts did not take place as part of a conversation, but might have been compared to another kind of vocalization altogether. Faber’s manipulation of the Euphonia entailed a strenuous set of activities behind the automaton (though, in truth, off to one side.) Its keyboard kept both of the inventor’s hands occupied at the machine’s “back,” while its foot-operated bellows had to steadily be pumped to produce airflow. Though requiring some imagination, one could imagine Faber and his creation having sex. At least one observer, it seems, did. In an article originally printed in the New York Paper, the author recounted how he “suggested to Mr. F[aber] that the costume and figure had better have been female.” This course of action offered practical mechanical-semiotic advantages “as the bustle would have given a well-placed and ample concealment for all the machinery now disenchantingly placed outside.” To the foregoing the writer added a clause: “—the performer sitting down naturally behind and playing her like a piano.”

Unidentified image of Faber’s Euphonia, public domain. c. 1870. The Euphonia was apparently sometimes exhibited with only the mannequin’s face in place, its body having been dispensed with.

Around 1870 the Euphonia was recast as a woman. By this time Herr Faber had been dead several years and his talking machine had passed on to a relative, also called Joseph, who outsourced the staged operation of the machine to his wife—Maria Faber. The transition from a male mannequin to a female mannequin (as well as the transition from a male operator to a female operator) throws into relief certain wrinkles in the gendered story of the Euphonia. Given that the Euphonia’s vocalizations could be read through the lens of sexualized domination, why had Faber himself not designed the mannequin as a woman in the first place? There are no pat answers. Perhaps the older, bookish, inventor believed the Turk could serve as an object of Western scientific domination without eliciting embarrassing and prurient commentary. Clearly, he underestimated the degree to which the idea of technological mastery already contained sexual overtones.

Little can be said about Joseph Faber’s life and work beyond 1846 though an entry for the inventor in the Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Österreich claimed that he took his life about 1850. Whatever the truth of Herr Faber’s fate, the Euphonia itself disappeared from public life around this same time and did not resurface for nearly two-and-a-half decades.

On the other hand, the idea of a female-presenting Euphonia, suggested by the New York Paper contributor in 1845, came to fruition as the machine was handed over to a female operator. If audiences imagined the spectacle of Euphonia-operation as a kind of erotic coupling, this new pairing would have been as troubling in its own way as Faber’s relationship to his Turk. What explains, then, the impulse to transition the Euphonia from androgyne to woman? Again, there are no pat answers. One solution to the enigma lies in the counter-factual: Whatever discomfiting sexual possibilities were broached in the Victorian mind by a woman’s mastery over a female automaton would have been greatly amplified by a woman’s mastery over a male one.

H.H.H. von Ograph “The Song of Mr. Phonograph” (New York: G Shirmer, 1878).

In these early exhibitions, the phonograph became “Mr. Phonograph.” In Chicago, for example, an exhibitor exclaimed “Halloa! Halloa!” into the apparatus before asking “Mr. Phonograph are you there?” “This salutation,” perspicaciously noted an attending Daily Tribune reporter “might have been addressed with great propriety to the ghosts at a spiritual seance…” In San Francisco, an exhibitor opened his demonstration by recording the message “Good morning, Mr. Phonograph.” Taking the bait, a Chronicle reporter described the subsequent playback: “‘Good morning, Mr. Phonograph,’ yelled Mr. Phonograph.”

In Atlanta, the phonograph was summoned “Mr. Phonograph, will you talk?” Mr. Phonograph obliged [“Wonder Agape!,” The Phonograph Puzzling Atlanta’s Citizens.” The Daily Constitution. June 22, 1878, 4]. At some point in 1878 the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company commissioned the printing of a piece of promotional sheet music “The Song of Mr. Phonograph.” The cover art for the song sheet featured a bizarrely anthropomorphized phonograph. The machine’s iron cylinder has been transformed into a head with eyes, while the mouthpiece and recording stylus have migrated outward and are grasped by two human hands. Mr. Phonograph’s attire, however, leaves no doubt as to his gender: He wears a collared shirt, vest, and jacket with long tails above; and stirrupped pants and dress boots below.

[Animal noises–cat, chicken, rooster, cow bird, followed by announcement by unidentified male voice, From UCSB Cylinder Archive]. Mr. Phonograph appealed not only to the professional exhibitors of the 1870s but to other members of the American public as well. One unnamed phonograph enthusiast recorded himself sometime before 1928 imitating the sounds of cats, hens, roosters and crows. Before signing off, he had his own conversation with “Mr. Phonograph.”

To understand the impulse to masculinize the phonograph, one must keep in mind the technology’s concrete mechanical capabilities. Unlike the Euphonia, the phonograph did not have a voice of its own, but could only repeat what was said to it. The men who exhibited the phonograph to a curious public were not able (like the Fabers before them) to sit in detached silence and manually prod their talking machines into talking. They were forced to speak to and with the phonograph. The machine faithfully addressed its handler with just as much (or as little) manly respect as that shown it, and the entire operation suggested to contemporaries the give-and-take of a conversation between equals. Not surprisingly, the phonograph became a man and a properly respectable one at that. Finally, the all-male contingent of exhibitors sent across the United States by the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company in 1878 invariably imparted to their phonographs their own male voices as they put the machine through its paces on stage. This, in itself, encouraged attribution of masculinity to the device.

The Euphonia and the phonograph both “talked.” The phonograph did so in a way mechanically-approximating the idealized bourgeois exchange of ideas and therefore “had” to be male. The Euphonia, on the other hand, spoke only as a function of its physical domination by its handler who wrung words from the instrument as if by torture. The Euphonia, then, “had” to be female.

The talking machines of the late nineteenth century as well as the media technologies that succeeded them emerged from a particular white, male, western and middle class culture.While changing in profound ways since the Victorian period, this culture has remained committed to the values of scientific mastery of nature; racial and gender hierarchies; and, especially, economic accumulation. But because the physical apparatus of talking machines has evolved so dramatically during this same period, it has been necessary to periodically renovate the ontology of mechanical speech in order to make it “safe” for the core values of the culture.

A fuller accounting of the politics of sound reproduction is possible but it depends on a more dynamic rendering of the interplay between practices, technologies and sonic understandings. It requires not only identifying speakers and listeners, but also placing them within the broader networks of people, things and ideas that impart to them moral content. It means attending—no less so than to texts and other representations—to the stories machines themselves tell when they enact the labor of speaking. We should listen to talking machines talking. But we should watch them as well.

—

Featured Image: from William C. Crum, ”Illustrated History of Wild Animals and Other Curiosities Contained in P.T. Barnum’s Great Travelling World’s Fair….” (New York: Wynkoop & Hallenbeck, 1874) 73. This image suggests that the later exhibitors of the Euphonia may have occasionally deviated from the gendered norms established by Joseph Faber, Sr. In image 4, a man—perhaps Joseph, Jr.— operates the Euphonia in its female form.

—

J. Martin Vest holds Bachelors and Masters degrees in History from Virginia Commonwealth University and a PhD in American History from the University of Michigan. His research interests range across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and are heavily influenced by the eclecticism and curiosity of working class storytelling. Past projects have explored Southside Virginia’s plank roads; the trope of insanity in American popular music; slavs in the American South; radical individualist “egoism;” twentieth century anarchists and modern “enchantment.” His dissertation, “Vox Machinae: Phonographs and the Birth of Sonic Modernity, 1870-1930,” charts the peculiar evolution of modern ideas about recorded sound, paying particular attention to the role of capitalism and mechanical technology in shaping the things said and believed about the stuff “in the grooves.”

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Only the Sound Itself?: Early Radio, Education, and Archives of “No-Sound”–Amanda Keeler

The Magical Post-Horn: A Trip to the BBC Archive Centre in Perivale–Leslie McMurtry

How Svengali Lost His Jewish Accent–Gayle Wald

- by napolinjb

- in American Studies, Amplifying Du Bois Forum, Article, Black Studies, Caribbean Studies, Diasporic Sound, Film/Movies/Cinema, Gender, Identity, Listening, Memory, Music, Philosophy, Queer Studies, Race, Sexuality, Sound, Sound Studies, Soundscapes, The Body, Theory/criticism, Voice

- 2 Comments

Shoo bop shoo bop, my baby, ooooo: W.E.B. Du Bois, Sigmund Freud & Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

It has been an abundant decade-plus (!!!) since Alexander Weheliye’s Phonographies “link[ed] the formal structure of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk to the contemporary mixing practices of DJs” (13) and we want to know how folks have thought about and listened with Du Bois in their work in the intervening years. How does Du Bois as DJ remix both the historiography and the contemporary praxis of sound studies? How does attention to Du Bois’s theories of race and sound encourage us to challenge the ways in which white supremacy has historically shaped American institutions, sensory orientations, and fields of study? What new futures emerge when we listen to Du Bois as a thinker and agent of sound?

Over the next two months, we will be sharing work that reimagines sound studies with Du Bois at the center. Pieces by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Kristin Moriah, Aaron Carter-Ényì, Austin Richey, Julie Beth Napolin, and Vanessa Valdés, move us toward a decolonized understanding and history of sound studies, showing us how has Du Bois been urging us to attune ourselves to it. To start the series from the beginning, click here.

Readers, today’s post by Julie Beth Napolin brings her trilogy to a close, exploring the echoes of black maternal sounding and listening she has amplified in Du Bois in Barry Jenkins’s Oscar-winning film Moonlight (2016).

Essay One: Listening to and as Contemporaries: W.E.B. Du Bois & Sigmund Freud

Essay Two: (T)racing Mother Listening: W.E.B. Du Bois & Sigmund Freud

–Jennifer Lynn Stoever and Liana Silva, Eds.

The theory of the acousmatic—the idea of a sound whose source is unseen, as it comes to us from Barthes, Chion, and Dolar—rests upon the mother tongue and the Oedipal scene, the dyad of mother and father. There is in “Do ba – na co – ba”–his great- great- grandmother’s song Du Bois remembers hearing passed down through his family–a transmission from the mother, but what kind of transmission? “There is no one extant autobiographical narrative of a female captive who survived the Middle Passage,” Hartman writes in “Venus in Two Acts” (3). History becomes, she continues, a project of “listening for the unsaid, translating misconstrued words” (3-4). The word-sounds “Do ba-na co-ba” are not the translation of a misconstrued word and they bolster a song of survival, of living on. But there is a silence there. “Do ba-na co-ba,” in a manner of speaking, survives the Middle Passage, and re-opens it as a primary channel of listening and receiving.

The Bantu woman was Du Bois’ grandfather’s grandmother, so many generations removed.

Returning to the vestiges of black motherhood in recent black cinema (including Jordan Peele’s Get Out and Barry Jenkin’s Moonlight), Rizvana Bradley argues that the loss of the mother “in black life more generally, as it repeats through cycles of material loss, … encapsulates racial slavery’s gendered social afterlife” (51). Bradley’s essay is crucial in retrieving the figure of the lost mother even in moments when the mother is absolutely elided as a character, not to appear visually. Horror more generally owes its immersive quality to the womb (enclosed spaces), but Bradley turns to black film form in particular to find in its mise-en-scène (such as in the gravitational field of the “sunken place”) maternal flesh and form.

In the compositional and formal strategies of The Souls of Black Folk, in the punctuated silences that open each chapter, there is a trace of the elided black maternal. The Bantu woman is lost not because Du Bois did not know her (he could not have), but because something of her song transmits a loss and theft that were not symbolic, but literal—a stolen and kidnapped maternal, rather than simply destroyed, as in the Oedipal mandate. It is crucial that the song that is at the core of Du Bois’ memory is transmitted along the maternal line. This maternal voicing is the unspoken wound of Du Bois’ text.

Spillers begins “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe” from the premise of non-Oedipal psycho-biographies, and these include not only the single mother, but the kidnapped mother. The quotation marks that surround the figure of the “black woman” for Spillers are “so loaded with mythical prepossession” that the agents it conceals cannot be clarified. Spillers takes particular aim at the infamous conclusions of the Moynihan report of 1965 that trace the roots of African American poverty to the figure of the single mother, the underachievement of lower class black males being linked in the report to black women.

In this way, black culture is thought to operate in a matriarchal pattern essentially out of step with a majority culture where a child’s identity and name, by definition, cannot be determined by the maternal line (66). As Lacan insists, it is the Father who gives a child both the Name and the symbolic Law (language). According to this configuration, Spillers argues, the child of the black mother can only be left in a haunting dis-identity. The implications for psychoanalysis are radical: Spillers begins the essay with a “stunning reversal of the castration thematic,” one that displaces its structure “to the territory of the Mother and Daughter, [and] becomes an aspect of the African-American female’s misnaming” (66). Among these misnamings is that black women are often not seen as “women,” omitted from the category and its political inflections. She is left castrated, politically impotent. For in this displacement, the subject positions of “male” and “female” lose—or fail to adhere to—their traditionally conceived symbolic integrity, and this loss begins with the historical experience aboard ship.

“waves and shadows,” image by Flickr User Albatrail

For Spillers, then, it is essential to trace this misnaming and undifferentiation of black women to the physical and psychic conditions of the Middle Passage. When Freud begins Civilization and Its Discontents, he notes an “oceanic feeling” engendered by religion. The oceanic is the longing for return to a pre-subjective state where one is united with all that is, before the cut that is birth and then language (indeed, the oceanic feeling is often attributed to song). Spillers’ move is to read the oceanic literally and structurally at once: there is the Atlantic Ocean and its Middle Passage. The oceanic, in this way, is de-subjectivating; it casts the subject out of itself in a terror of undifferentiation that does not cease with landfall.

But Spillers also implies that, in that (sexual) undifferentiation, a radical political potential can be retrieved. It is not that black feminism retrieves for her a sexual differentiation after becoming an ambiguous thing. It would not be “woman” in any traditional sense, for that New World category rests upon the violence Spillers seeks to describe. Above all, it would not be easy to name.

Du Bois certainly takes up the Father in his poetic epigraphs. But in ending with the Bantu woman’s song—as it seems to anatomize all of the other songs he describes—Du Bois upholds himself as being named by the maternal line. He is unable or perhaps unwilling to make a clarified place for a black female political agent. If we listen with ear’s pricked, we find that she is the submerged, oceanic condition for his speech.

By way of an open-ended conclusion, we can recall the sound of the ocean that punctuates Jenkin’s stunningly lyrical and psychologically complex coming-of-age film, Moonlight. The ocean provides the anchoring location for the psychological action, but also its aesthetic locus, the beginnings of its cinematic language. The sound of the ocean continually marks a desire for “return” to maternal undifferentiation and oneness, and yet, it provides the space for two embodied memories that cannot be compassed by traumatic separation. In the first, a father-like figure, Juan, embraces a young boy, Little, to allow him to float in a nearly baptismal scene of second birth, and in a second scene at the shore, Little experiences with his friend, Kevin, sexual gratification, a coming into his body as a site of pleasure.

The conclusion of the film posits these moments as being in the past. We had experienced them as contemporary, but only later realize they are a well of memory for a now-adult subject who does not know himself. I want to focus, then, on the film’s conclusion, after Kevin and Little (now named Black, his adult re-renaming), meet again after many years. Kevin calls Little/Black on the phone, a defining gesture of reaching out erotically and acousmatically with voices. We later learn that he calls because Kevin has heard an old song that reminded of him of his lost friend. By this voice or call, Black is brought somewhere back to his moment of break to become Little again, as if something in the past must be recuperated for the present. As he drives down the open road to find Kevin, the music of Caetano Veloso soars.

We can’t be sure if this is extra-diegetic or diegetic music. To be sure, Black would never listen to such a song on his stereo. And yet, the song seems to emanate directly from its affective space. In the language of literature, it is a “free-indirect style,” part character and part author; the film is hearing Black/Little feel. He’s in a space of haunting melody, drenched in personal memory, whose principle scene had been the Florida shore, the ocean lapping providing a (maternal) containing motif for the film, now transmuted into song.

The oceanic, Spillers might remind us, is violent, echoing the passages that made it possible for these two black boys to be there. But the sound is also amniotic, a space of maternal longing, particularly for a character who, in Bradley’s estimation, is positioned as pathological, injured by the missing mother who is, in turn, indicted by the film’s imaginary. To some extent, Moonlight participates in the mother’s misnaming: it cannot see the structures that ensure her lostness. But the film does also push towards some mode of melancholia that, as Michael B. Gillespie argues of Jenkins’ earlier work, would cease to be depressive. Jenkins’ aesthetic practice is transformative, Gillespie suggesting that we use Flatley’s term, “antidepressive melancholia,” as it’s with a stake in the personal past but turned towards the collective future (106).

When the two boys, now men, meet again, several sounds punctuate the scene. They are not words or even phonemes, yet “speak” to provide a sonic geography of feeling that includes or “holds” the viewer, as Ashon Crawley might suggest. Among them is the sound of the bell on the door, which marks hello and goodbye, entry and exit, coming and going (or “fort-da” in Freud’s lexicon). When Black enters the diner, he is still “Black.” It is only when remembering what happened at the shore, then to say that no man has touched him since, that he becomes Little. He discloses this truth on behalf of a potential in present and a still-nascent future. Kevin cooks for Black, and Jenkins’ is careful to amplify the sound of the spoon stirring. He provides for Black, the film locating Kevin, a male, within the coordinates of maternal care. The sonic crux of the scene—no longer primal, no longer traumatic—is when Kevin plays the song on the jukebox that had drawn him to call to Little/Black in the first place. “Hello, stranger,” Barbara Lewis croons, “it seems like a mighty long time. Shoo bop shoo bop, my baby, ooooo.”

In listening to a song that is from our past, Newtonian time collapses, a shock running from past to present. The film never discloses whether these two had once heard this song together before. It is more likely that its affective map impacts Kevin, that he hears in its melancholic sound a nascence, and with it, a longing to retrieve his own past and repair. Lewis herself, singing in the sixties, is a recalling an already eclipsed fifties doo-wop. The phonemes circle back to their beginnings in “Do ba- na co-ba.” Such sounds are to be opposed to the shot of Little’s mother yelling at him (presumably a slur). There, the sound had cut out of the scene, which recurs for Little in a traumatic nightmare.

In contrast to that violent naming, the boys’ intimacy was defined by, to use Kevin Quashie’s term, “quiet,” a sense of interiority Michael Gillespie explores in his analysis of Jenkins’ first feature film, Medicine for Melancholy. Shakira Holt and Chris Chien called this dynamic in Chiron and Juan’s relationship “silence as a form of intimate conversance” in their 2017 post about Moonlight. There is a queer intimacy revived apart from trauma, triangulated by a black woman’s voice, paired with male harmonies, that resonate acousmatically from the jukebox to hold and contain the scene. For psychoanalytic theories of voice, containment is the essential maternal gesture of song.

We begin to wonder what might be possible for the feminine were it to be separated from the maternal dimension, a potential that Jenkins does not explore in this particular film in his oeuvre (as he does in Medicine for Melancholy, for example); each of the women in Moonlight “mother” to some extent. Nonetheless, he disperses the maternal function across male and female subjects, particularly in moments when the film resists depression. In listening with ears pricked, as with Du Bois’ epigraphs, the voices cease to belong to an individual, to be male voices or female voices, but become plural and pluralistic. It becomes possible to ground a politics of listening to the past for remaking in the present in that sound.

—

I would like to thank Michael B. Gillespie, Amanda Holmes, and Jennifer Stoever for their incredible scholarly assistance and comments in writing this essay trilogy.

—

Julie Beth Napolin is Assistant Professor of Literary Studies at The New School, a musician, and radio producer. She received a PhD in Rhetoric from the University of California, Berkeley. Her work participates in the fields of sound studies, literary modernism and aesthetic philosophy, asking what practices and philosophies of listening can tell us about the novel as form. She served as Associate Editor of Digital Yoknapatawpha and is writing a book manuscript on listening, race, and memory in the works of Conrad, Du Bois, and Faulkner titled The Fact of Resonance. Her work has appeared in qui parle, Fifty Years After Faulkner (ed. Jay Watson and Ann Abadie), and Vibratory Modernism (ed. Shelley Trower and Anthony Enns).

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Moonlight’s Orchestral Manoeuvers: A duet by Shakira Holt and Christopher Chien

“A Sinister Resonance”: Joseph Conrad’s Malay Ear and Auditory Cultural Studies–Julie Beth Napolin

“Scenes of Subjection: Women’s Voices Narrating Black Death“–Julie Beth Napolin

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

- Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments