Sonic Homes: The Sonic/Racial Intimacy of Black and Brown Banda Music in Southern California

This series listens to the political, gendered, queer(ed), racial engagements and class entanglements involved in proclaiming out loud: La-TIN-x. ChI-ca-NA. La-TI-ne. ChI-ca-n-@. Xi-can-x. Funded by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation as part of the Crossing Latinidades Humanities Research Initiative, the Latinx Sound Cultures Studies Working Group critically considers the role of sound and listening in our formation as political subjects. Through both a comparative and cross-regional lens, we invite Latinx Sound Scholars to join us as we dialogue about our place within the larger fields of Chicanx/Latinx Studies and Sound Studies. We are delighted to publish our initial musings with Sounding Out!, a forum that has long prioritized sound from a queered, racial, working-class and “always-from-below” epistemological standpoint. —Ed. Dolores Inés Casillas

—

No tengo nada de sangre de Mexico. Soy afro americano.

(I have no Mexican blood. I am African American.)

El Compa Negro (Ryhan Lowery)

The grain is the body in the singing voice, in the writing hand, in the performing limb.

Roland Barthes (The Grain of the Voice,1971)

***This post is co-authored by Sara Veronica Hinojos and Alex Mireles

Sarah La Morena (Sarah the Black woman), or Sarah Palafox, was adopted and raised by a Mexican family in Mexico. At the age of five, she moved to Riverside, California, a predominantly Mexican city an hour east of Compton. Palafox started singing as a way to express the racism she faced as a child in Southern California, feeling caught between her Black appearance and her Mexican sound. She found her voice in church, a nurturing environment where she could be herself, surrounded by her family’s love. She gained attention with a viral video of her rendition of Jenni Rivera’s “Que Me Vas a Dar.” Palafox delivers each note with profound emotion and precision, leaving even the accompanying mariachi violinist in awe.

Similarly, El Compa Negro (The Black Friend/Homie) or Rhyan Lowery heard the sounds of banda coming from his neighbor’s backyard in Compton; a historically Black-populated city with a current Mexican majority. Lowery couldn’t shake the song out of his head and learned the song’s Spanish-language lyrics. Like Palafox, videos of him singing in Spanish during high school made him a viral sensation. “They called me ‘el compa negro’ (…) All I heard was ‘blah blah blah negro or negro’ and I wasn’t having it until they explained to me what it meant. And I was like ‘ok, cool’.”

The sonic stylings of El Compa Negro and Sarah La Morena within the banda genre enable transcultural connections beyond the pan-Chicano-Mexican-Central American popularity of tecnobanda and la quebradita. The 1990s banda craze, writes George Lipsitz “challenged traditional categories of citizenship and culture on both sides of the US-Mexico border.” Banda music might sound like it was established south of the border, but multicultural listeners and dancers continue to influence its vibrations. Pop stars like Snoop Dogg, Shakira, Bad Bunny, and Karol G have released (tokenized) songs with Mexican-tinged, banda-recognizable beats. Yet, both El Compa and Sarah demonstrate a form of musical Black/Brown, working-class intimacy. Their respective musics are much less about a pop star (duet) kind of solidarity and much more about a deep knowing, a sensibility among working-class cultures and othered people that resonates through the aesthetics of sound. As Karen Tongson writes in Relocations: Queer Suburban Imaginaries, about her experience of “queer, brown, immigrant musical discovery” in Riverside, the hometown she shares with Sarah La Morena: “It is the music that inspires us to ask questions” (26).

Certainly, US Mexican immigrant culture does not have the same (mainstream) cultural caché as African American culture, unless somehow softened or filtered. Jalapeños get “de-spicifed“; pre-made Día de Los Muertos altares are now at Wal-Mart, and huipiles are available as fast-fashioned “peasant blouse;” filtering out their Mexican-indigenous origins. Thus, classics like “La Yaquesita” and originals like “Yo Soy Compton” heard through the grain of Black voices affirm the possibilities of U.S. Mexican belonging or what D. Travers Scott characterizes as a form of “intimate intersubjectivities;” rooted in long-established Black/Brown co-existences across the borderlands and city barrios. Turning the volume up on these artists serves an important counterpoint to Latino anti-Black racism.

Their voices, blending with brass and tambora, embody a Black-Brown sonic and symbolic solidarity, or spatial entitlement. As theorized by Gaye Theresa Johnson in Spaces of Conflict, Sounds of Solidarity, innovative applications of technology, creativity, and space foster new collectives which, even when “unheard” by historians, assert social citizenship and pave the way for new working-class political futures. In the contested neighborhoods of greater Los Angeles, Black and Brown communities are often pitted against one another through processes of containment and confinement leading to competitions for jobs, housing, status, and political power. Yet, they share the experiences of labor exploitation, housing segregation, and cultural vilification. Filmed in the intimate settings of backyards, the viral videos underscore Black/Brown hood/barrio soundscapes as multi-generational, familial, and culturally hybrid. Home is where shared class, racial, and gender politics are negotiated and resolved.

Asserting Black identity and the choice to perform in Spanish creates a unique visual and auditory experience within the Mexican-dominant world of banda. In fact, in 2024, Lowery made history as the first Spanish-language artist signed by Death Row Records, a label known primarily for hip hop. The lively rhythms of banda – oompah-oompah-oompah – offers both banda and hip hop listeners a new orientation to discern the racial-cultural politics of broader Los Angeles.

Like the mid-century Haitian-Mexican bolero singer Antonia del Carmen Peregrino Álvarez, alias “Toña La Negra,” the added tags “Negro” and “la Morena” signals Black singers’ recognition of the meaning(s) of their racial difference within the transnational Mexican music scene. The auditory discomfort that their vocal grain might cause is named and thus recognized as the persistent colorism of listeners at large. Lowery describes his initial unease with the given “Compa Negro” nickname. “My Mexican friends always tell me ‘Hey, compa negro, you’re Mexican, man. God just left you in the oven a little too long.’” The harassment came from both Black peers and Mexicans alike, for liking banda, dating Latinas, or dressing “like a Mexican.” “They would say, ‘You hate being Black. Self-hate. Self-hate. I’m like man it ain’t that I self-hate, it’s just that I embrace something. I took the time to have an open mind and study something, you know?” His way of being made sense in the context of a Compton teenage experience. “Becoming Mexican” by way of musical/cultural engagement surpassed skin tone-deep and nationalist differences.

Or, as Mexican ranchera singer Chavela Vargas–born in Costa Rica–famously asserted, “Mexicans are born wherever the hell they want!” Try listening to Juan Gabriel’s “Amor Eterno” to find out. Black creatives like Evander, Vaquera Canela, and Terry Turner are just a few more examples of Black mexicanidad. Yessica Garcia Hernandez reminds us that Black and Brown sonic solidarities have been the driving pulse of US popular music. She argues, “Home and sound is acknowledging that both corridos, hip-hop, and G-funk relationally, has formed paisas.”

El Compa Negro’s “Verde es Vida,” a tribute to California’s weed culture, lowriders, and corridos, booms loudly. The song begins with an accordion playing reggae rhythms, soon interrupted by percussion, guitars, and El Compa’s fast-paced verses. About a minute in, the accordion slows the tempo with a few reggae notes before the vocals return, reintroducing the corrido rhythm: “Hoy andamos en LA bien tranquilitos. En el lowrider escuchando corridos.” The reggae-corrido fusion ends with the familiar “pom pom pom pom!” of the drums, typical of banda and corrido finales, as the accordion plays its last note. Through Lowery’s reggae corrido, we hear his “sonic home” rooted in Black and Brown Los Angeles.

—

Featured Image: still from Sarah La Morena’s “La Llorona” (2020)

—

Sara Veronica Hinojos is an Assistant Professor of Media Studies and on the advisory board for Latin American and Latino Studies at Queens College, CUNY. Her research focuses on representations of Chicanx and Latinx within popular film and television with an emphasis on gender, race, language politics, and humor studies. She is currently working on a book manuscript that investigates the racial function of linguistic “accents” within media, called: GWAT?!: Chicanx Mediated Race, Gender, and “Accents” in the US.

Alex Mireles is a PhD student in the Department of Feminist Studies at UC Santa Barbara. She writes on Latinx identity and queerness, labor, and global capitalism through aesthetic movements in fashion, beauty, media, and visual cultures. Her dissertation explores the queer potential and world-making capabilities of Chicanx popular culture through Mexican regional music, social media, queer nightlife, and film.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Boom! Boom! Boom!: Banda, Dissident Vibrations, and Sonic Gentrification in Mazatlán—Kristie Valdez-Guillen

Listening to MAGA Politics within US/Mexico’s Lucha Libre –Esther Díaz Martín and Rebeca Rivas

Ronca Realness: Voices that Sound the Sucia Body—Cloe Gentile Reyes

Echoes in Transit: Loudly Waiting at the Paso del Norte Border Region—José Manuel Flores & Dolores Inés Casillas

Sounding Out! Podcast #28: Off the 60: A Mix-Tape Dedication to Los Angeles–Jennifer Stoever

“Caught a Vibe”: TikTok and The Sonic Germ of Viral Success

“When I wake up, I can’t even stay up/I slept through the day, fuck/I’m not getting younger,” laments Willow Smith of The Anxiety on “Meet Me at Our Spot,” a track released through MSFTSMusic and Roc Nation in March of 2020. Despite the song’s nature as a “sludgy alternative track with emo undertones that hits at the zeitgeist,” “Meet Me at Our Spot” received very little attention after its initial release and did not chart until the summer of 2021, when it went viral on TikTok as part of a dance trend. The short-form video app which exploded in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, catalyzed the track’s latent rise to success where it reached no. 21 on the US Billboard Hot 100, becoming Willow’s highest charting song since her 2010 hit, “Whip My Hair”.

The app currently known as TikTok began as Musical.ly, which was shuttered in 2017 and then rebranded in 2018. By March of 2021, the app boasted one billion worldwide monthly users, indicative of a growth rate of about 180%. This explosion was in many ways catalyzed by successive lockdowns during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the relaxation and subsequent abandonment of COVID mitigation measures, the app has retained a large volume of its users, remaining one of the highest grossing apps in the iOS environment. TikTok’s viral success (both as noun and adjective) has worked to create a kind of vibe economy in which artists are now subject to producing a particular type of sound in order to be rendered legible to the pop charts.

For anyone who has yet to succumb to the TikTok trap, allow me to offer you a brief summary of how it functions. Upon opening it, you are instantly fed content. Devoid of any obvious internal operating logic, it is the media equivalent of drinking from a fire hose. Immersive and fast-paced, users vertically scroll through videos that take up their entire screen. Within five minutes of swiping, you can–if your algorithm is anything like mine–see: cute pet videos, protests against police brutality, HypeHouse dance trends, thirst traps, contemporary music, therapy tips, attractive men chopping wood, attractive women lifting weights, and anything else you can fathom. Since its shift from Musical.ly, the app has also been a staging ground for popular music hits such as Lil Nas X’s’ “Old Town Road”, Lizzo’s “Good As Hell”, and, recently, Harry Styles’ “As It Was.”

The app, which is the perfect–if chaotic–fusion of both radio and video is enmeshed in a wider media ecosystem where social networking and platform capitalism converge, and as a result, it seems that TikTok is changing the music industry in at least three distinct ways:

First, it affects our music consumption habits. After hearing a snippet of a song used for a TikTok, users are more likely to queue it up on their streaming platform of choice for another, more complete listen. Unlike those platforms, where algorithms work to feed a listener more of what they’ve already heard, TikTok feeds a listener new content. As a result, there’s no definitive likelihood that you’ve previously heard the track being used as a sound. Therefore, TikTok works the way that Spotify used to: as a mechanism for discovery.

Second, TikTok is changing the nature of the single. Rather than relying upon a label as the engine behind a song’s success, TikTok disseminates tracks–or sounds as they’re referred to in the app–widely, determining a song’s success or role as a debut within a series of clicks. Particularly during the pandemic, when musicians were unable to tour, TikTok’s relationship to the industry became even more salient. Artists sought new ways to share and promote their music, taking to TikTok to release singles, livestream concerts, and engage with fans. Moreover, Spotify’s increasingly capacious playlist archive began to boast a variety of tracklists with titles such as, “Best TikTok Songs 2019-2022”, “TikTok Songs You Can’t Get Out Of Your Head”, and “TikTok Songs that Are Actually Good” among others. The creation and maintenance of this feedback loop between TikTok and Spotify demonstrates not only the centrality of social media ecosystems as driving current popular music success, but also the way that these technologies work in harmony to promote, sustain, or suppress interest in a particular tune.

Most notoriously, the bridge of Olivia Rodrigo’s “drivers license”, went viral as a sound on TikTok in January 2021 and subsequently almost broke the internet. Critics have praised this 24-second section as the highlight of the song, underscoring Rodrigo’s pleading soprano vocals layered over moody, syncopated digital drums. Shortly after it was released, the song shattered Spotify’s record for single-day streams for a non-holiday song. New York Times writer Joe Coscarelli notes of Rodrigo’s success, “TikTok videos led to social media posts, which led to streams, which led to news articles , and back around again, generating an unbeatable feedback loop.”

And third, where songwriting was once oriented towards the creation of a narrative, TikTok’s influence has led artists to a songwriting practice that centers on producing a mood. For The New Yorker, Kyle Chayka argues that vibes are “a rebuke to the truism that people want narratives,” suggesting that the era of the vibe indicates a shift in online culture. He argues that what brings people online is the search for “moments of audiovisual eloquence,” not narrative. Thus, on the one hand, media have become more immersive in order to take us out of our daily preoccupations. On the other, media have taken on a distinct shape so that they can be engaged while doing something else. In other words, media have adapted to an environment wherein the dominant mode of consumption is keyed toward distraction via atmosphere.

Despite their relatively recent resurgence in contemporary discourse, vibes have a rich conceptual history in the United States. Once a shorthand for “vibration” endemic to West Coast hippie vernacular, “vibes” have now come to mean almost anything. In his work on machine learning and the novel form, Peli Grietzer theorizes the vibe by drawing on musician Ezra Koenig’s early aughts blog, “Internet Vibes.” Koenig writes, “A vibe turns out to be something like “local colour,” with a historical dimension. What gives a vibe “authenticity” is its ability to evoke–using a small number of disparate elements–a certain time, place, and milieu, a certain nexus of historic, geographic, and cultural forces.” In his work for Real Life, software engineer Ludwig Yeetgenstein defines the vibe as “something that’s difficult to pin down precisely in words but that’s evoked by a loose collection of ideas, concepts, and things that can be identified by intuition rather than logic.” Where Mitch Thereiau argues that the vibe might just merely be a vocabulary tick of the present moment, Robin James suggests that vibes are not only here to stay, but have in fact been known by many other names before. Black diasporic cultures, in particular, have long believed sound and its “vibrations had the power to produce new possibilities of social attunement and new modes of living,” as Gayle Wald’s “Soul Vibrations: Black Music and Black Freedom in Sound and Space,” attests (674). We might then consider TikTok a key method of dissemination for a maximalist, digital variant of something like Martin Heidegger’s concept of mood (stimmung), or Karen Tongson’s “remote intimacy.” The vibe is both indeterminate and multiple, a status to be achieved and the mood that produces it; vibes seek to promote and diffuse feelings through time and space.

Much current discourse around vibes insists that they interfere with, or even discourage academic interpretation. While some people are able to experience and identify the vibe—perform a vibe check, if you will—vibes defy traditional forms of academic analysis. As Vanessa Valdés points out, “In a post-Enlightenment world that places emphasis on logic and reason, there exists a demand that everything be explained, be made legible.” That the vibe works with a certain degree of strategic nebulousness might in fact be one of its greatest assets.

Vibes resist tidy classification and can thus be named across a variety of circumstances and conditions. Although we might think of the action of ‘vibing’ as embodied, and the term vibration quite literally refers to the physical properties of sound waves and their travel through various mediums, the vibe through which those actions are produced does not itself have to be material. Sometimes, they name a genre of feeling or energy: cursed vibes or cottagecore vibes. Sometimes, they function as a statement of identification: I vibe with that, or in the case of 2 Chainz’s 2016 hit, “it’s a vibe.” Sometimes, vibes are exchanged: you can give one, you can catch one, you can check one, So, while things like energy and mood—which are often taken as cognates for vibes—work to imagine, name, and evoke emotions, vibes are instead invitations.

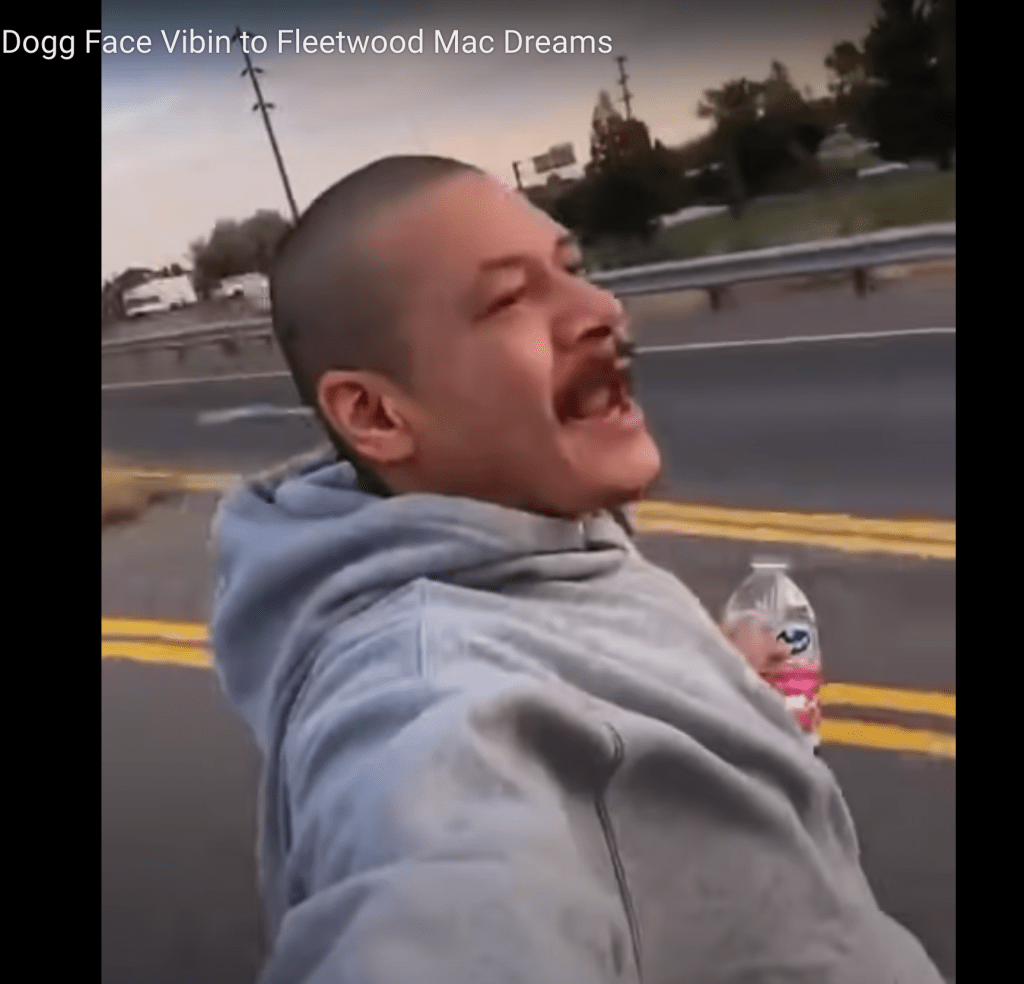

Not only do vibes serve as a prompt for an attempt at articulating experience, they are also invitations to co-presently experience what seems inarticulable. By capturing patterns in media and culture in order to produce a coherent image/sound assemblage, the production of a vibe is predicated upon the ability to draw upon large swathes of visual, aural, and environmental data. Take for example, the story of Nathan Apodaca, known by his TikTok handle as: 420doggface208. After posting a video of himself listening to Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” while drinking cranberry juice and riding a longboard, Apodaca went viral, amassing something like 30 million views in mere hours. This subsequently sparked a trend in which TikTok users posted videos of themselves doing the same thing, using “Dreams” as the sound. According to Billboard, this sparked the largest ever streaming week for Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 hit with over 8.47 million streams. Of his overnight success, Apodaca says, “it’s just a video that everyone felt a vibe with.” To invoke a vibe is thus to make a particular atmosphere more comprehensible to someone else, producing a resonant effect that draws people together.

As both an extension and tool of culture, vibes are produced by and imbricated within broader social, political, and economic matrices. Recorded music has always been confined—for better and worse—to the technologies, formats, and mediums through which it has been produced for commercial sale. On a platform like TikTok, wherein the emphasis is on potentially quirky microsections of songs, artists are invited to key their work towards those parameters in order to maximize commercial success. Nowadays, pop songs are produced with an eye towards their ability to go viral, be remixed, re-released with a feature verse, meme’d, or included in a mashup. As such, when an artist ‘blows up’ on TikTok, it does not necessarily mean that the sound of the song is good (whatever that might mean). Rather, it might instead be the case that a hybrid assemblage of sound, performance, narrative, and image has coalesced successfully into an atmosphere or texture – that we recognize as a/the vibe – something that not only resonates but also sells well. As TikTok’s success continues to proliferate, the app is continually being developed in ways that make it an indispensable part of the popular music industry’s ecosystem. Whether by exposing users to new musical content through the circulation of sounds, or capitalizing upon the speed at which the app moves to brand a song a ‘single’ before it’s even released, TikTok leverages the vibe to get users to listen differently.

@jimmyfallon This one’s for you @420doggface208 #cranberrydreams#doggface208#dogfacechallenge♬ original sound – Jimmy Fallon

We might indeed consider vibes to be conceptual, affective algorithms created in the interstice between lived experience and new media. “Meet Me At Our Spot,” the track through which I’ve framed this article, is full of allusions to youth culture: drunk texts, anxiety over aging, and late-night drives on the 405. It is buoyed by a propulsive bass line that thumps with a restless energy and evokes a mood of escapism. Willow Smith’s intriguing timbre and the pleasing harmonies she achieves with Tyler Cole invite listeners to ride shotgun. For the two minutes and twenty-two seconds of the song, we are immersed within their world. In the final measures the pop of the snare recedes into the background and Tyler’s voice fades away. The vibe of the track – both sonically and thematically – is predicated on the experience of a few, fleeting moments. Willow leaves us with a final provocation, one that resonates with popular music’s current mode: “Caught a vibe, baby are you coming for the ride?”

—

Featured Image: Screencap of Nathan Apodaca’s viral TikTok post, courtesy of SO! eds.

—

Jay Jolles is a PhD candidate in American Studies at the College of William and Mary currently at work on a dissertation tentatively titled “Man, Music, and Machine: Audio Culture in a/the Digital Age.” He is an interdisciplinary scholar with interests in a wide range of fields including 20th and 21st century literature and culture, critical theory, comparative media studies, and musicology. Jay’s scholarly work has appeared in or is forthcoming from The Los Angeles Review of Books, U.S. Studies Online, and Comparative American Studies. His essays can be found in Per Contra, The Atticus Review, and Pidgeonholes, among others. Prior to his time at William and Mary, he was an adjunct professor of English at Drexel University and Rutgers University-Camden.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Listen to yourself!: Spotify, Ancestry DNA, and the Fortunes of Race Science in the Twenty-First Century”–Alexander W. Cohen

Evoking the Object: Physicality in the Digital Age of Music–-Primus Luta

“Music is not Bread: A Comment on the Economics of Podcasting”-Andreas Duus Pape

“Pushing Record: Labors of Love, and the iTunes Playlist”–Aaron Trammell

Critical bandwidths: hearing #metoo and the construction of a listening public on the web–Milena Droumeva

TiK ToK: Post-Crash Party Pop, Compulsory Presentism and the 2008 Financial Collapse—Dan DiPiero (The other “TikTok”! The people need to know!)

Recent Comments