Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

.

16 years in, we’re still here, listening hard for each thump, rasp, and rattle of the drum to amplify for our readers. Keep the pressure coming louder and louder for us to propagate, and look out for our print edition, Power in Listening: The Sounding Out! Reader to drop in August 2026 from NYU Press! –JS, Ed-in-Chief

Here, beginning with number 10, are our Top 10 posts released in 2025 (as of 12/13/25)!

—

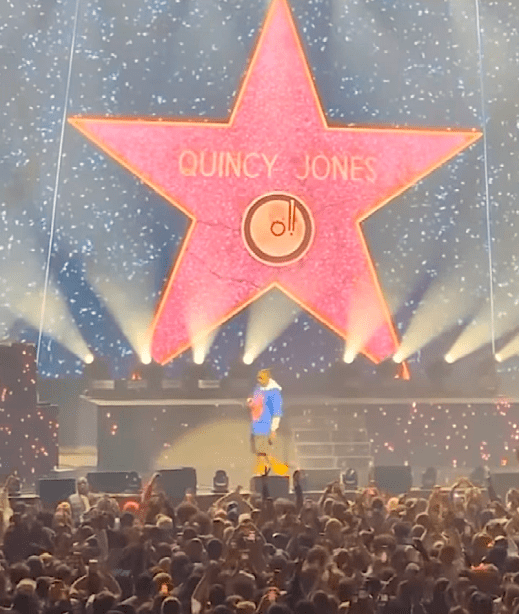

(10). The Sonic Rhetoric of Quincy Jones (feat. Nasir Jones)

By Jaquial Durham

“The passing of Quincy Jones has left a silence that feels almost impossible to fill. Every time I play Thriller at home now, it’s no longer just a celebration of his unparalleled artistry. It’s a ritual to sit with his legacy, listen more closely, and honor how his music shaped the sound of memory itself. With each spin of the record, my family and I find ourselves inside his arrangements, held by their richness, precision, and sense of story as though the music is breathing with us, speaking back across time. Jones’s work was never just production; it was communication. A language of sound connected us to melody and beat and the fuller spectrum of emotion, culture, and memory that lives in Black music.. .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(9). The Techno-Woman Warrior: K-pop and the Sound of Asian Futurism

By Hoon Lee

“As a ’90s kid, I remember too well us school kids singing and dancing to the songs at the top of the charts on music shows such as Ingigayo (인기가요) and Music Bank (뮤직뱅크). It was what one might call the “pre-K-pop” era: there were a lot of solo artists performing in various genres, and the notion of idol culture as we know it now was only fledgling. Without the mass production system or the global distribution that has come to be the norm in today’s K-pop, first generation idol groups around the new millennium—H.O.T., Fin.K.L, god, Sechs Kies, S.E.S.—not only set up these business models and standards, but also inspired the music and aesthetics of later generations. The group aespa’s cover of “Dreams Come True” by S.E.S. is an exemplar case, and NewJeans, with their unflinching Y2K aesthetics and sound, take us back to the millennial through and through. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(8).Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

By Daimys García

“I am always listening for María: I find her most in the traces of words.

Trained as a literary scholar, I relish in the contours of stories; I savor the nuances found between crevices of language and the shades of implication when those languages are strung together. It is no surprise, then, that since the death of my friend and mentor María Lugones, I have turned to many books, particularly her book, Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes: Theorizing Coalition Against Multiple Oppression, to feel connected to her. I have struggled, though, to write about her, talk about her, even think about her for many years. It wasn’t until I found a passage about spirits and hauntings in Cuban-American writer and artist Ana Menéndez’s novel The Apartment that I found language to describe a way through the grief of the last five years. . .”

[Click here to read more]

——

(7). The Sounds of Equality: Reciting Resilience, Singing Revolutions

by Mukesh Kulriya

“When the pandemic hit the world in late 2019, the concept of lockdown ceased the social life of the people and their communities. In these unprecedented circumstances, a video from Italy took the internet. People in Italian towns such as Siena, Benevento, Turin, and Rome were singing from their windows and balconies, which raised morale. The song “Bella Ciao,” an old partisan Italian song, became an anthem of hope against adversity. This anti-fascist song was popularized during the mid-20th century across the globe as a part of progressive movements. Following this, people in many countries around the world created their renditions of “Bella Ciao” in Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish, Persian, French, Spanish, Armenian, German, Portuguese, Russian, and within India in languages such as Punjabi, Marathi, Bangla, and even in sign language renditions. It was such an apt moment that captured the idea of empathy, solidarity, and the human need for community. This moment was still resonating with me when I was approached by Goethe Institut, New Delhi, to work on music and protest, and create The Music Library. I knew what I needed to do. . . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(6).SO! Reads: Zeynep Bulut’s Building a Voice: Sound, Surface, Skin

—by Enikő Deptuch Vághy

“Voice and sound theorist Zeynep Bulut’s Building a Voice: Sound, Surface, Skin (Goldsmiths Press, 2025) is a remarkable work that reconfigures the ways we define “voice.” The text is organized into three sections—Part 1: Plastic (Emergence of Voice as Skin), Part 2: Electric (Embodiment of Voice as Skin), and Part 3: Haptic (Mediation of Voice as Skin)—each articulating Bulut’s exploration of the simultaneously personal and collaborative ways voice evolves among various sonic entities and environments. Through analyses of several artistic works that experiment with sound, Bulut successfully highlights the social effects of these pieces and how they alter our expectations of what it means to communicate and be understood.”

[Click here to read more]

—

(5). Clapping Back: Responses from Sound Studies to Censorship & Silencing

by MLA Sound Studies Executive Forum

“The MS Sound Forum invites papers for a guaranteed session at the Modern Language Association’s annual conference in Toronto, Canada in January 2026. The session responds in part to the MLA Executive Council’s refusal to allow debate or a vote on Resolution 2025-1, which supported the international “Boycott, Divest, and Sanction” (BDS) Movement for Palestinian rights against the ongoing genocide in Gaza. In light of the Council’s suppression of debate, some of the Sound Forum Executive Committee members decided to resign in protest while others remained to hold the MLA accountable for its undemocratic procedures. To acknowledge and respect the decision of those who left, the remaining members chose not to immediately fill the vacancies to let the parting members’ silence speak.. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

—(4). “Just for a Few Hours, We Was Free”: The Blues and Mapping Freedom in Sinners (2025)

by Juston Burton

“In the 2025 blockbuster Sinners, Ryan Coogler has a vampire story to tell. But before he can begin, he needs to tell another story—a blues one. Sinners opens with a voiceover thesis statement performed by Wunmi Mosaku (who plays Annie in the film—more on her below) about the work the blues can do, then rambles the narrative through and around 1932 Clarksdale, eventually settling into a juke joint outside of town. Here, the blues story builds to a frenzied climax, ultimately conjuring the vampires propelling the film’s second half. It’s those vampires that most immediately register as cinematic spectacle, but Coogler’s impetus to film in IMAX and leverage all of his professional relationships for the movie wasn’t the monsters—it was to showcase the blues at a scale the music deserves. In Sinners, the blues takes center stage as a generative sonic practice, sound that creates space to be and to know in the crevices of the material world, providing passage between oppression and freedom, life and death, past and future, and good and evil. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

—(3). “Keep it Weird”: Listening with Jonathan Sterne (1970-2025)

by Benjamin Tausig

“Dr. Jonathan Sterne passed away earlier this year. He was, in many ways, a model scholar and colleague.

The intellectual ferment of the field now called “sound studies” is often traced to the sonic ecologists of the 1960s, but the theoretical energy of the early 2000s, generated by figures such as Ana Maria Ochoa, Alexander Weheliye, Emily Thompson, Trevor Pinch (1952-2021), and of course Jonathan Sterne, was necessary for the field to gain interdisciplinary traction in the twenty-first century. Sterne’s The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Duke University Press: 2003) was perhaps the single-most important book in this regard.

Trained in communications, and working in departments of communication, first at Pitt and later McGill, Sterne oriented his work toward media studies, and indeed, The Audible Past is principally about mediation. It poses questions about the role of sound in the history of mediation that earlier generations of sound studies had tended to elide, especially regarding the contingent and often cultural role of the human ear in reception. These questions opened the door for anthropologists, historians, communications scholars and ethnomusicologists in particular to think and even identify with sound studies, and many of us who were trained in the 2000s did so enthusiastically, with Sterne’s writing a lodestar.. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(2). Faithful Listening: Notes Toward a Latinx Listening Methodology

by Wanda Alarcón, Dolores Inés Casillas, Esther Díaz Martín, Sara Veronica Hinojos, Cloe Gentile Reyes

“For weeks, we have been inundated with executive orders (220 at last count), alarming budget cuts (from science and the arts to our national parks), stupendous tariff hikes, the defunding of DEI-anything, the banning of transgender troops, a Congressional renaming of the Gulf of Mexico, terrifying ICE raids, and sadly, a refreshed MAGA constituency with a reinvigorated anti-immigrant public sentiment. Worse, the handlers for the White House’s social media publish sinister MAGA-directed memes, GIFs across their social channels. These reputed Public Service Announcements (PSAs), under President Trump’s second term, ruthlessly go after immigrants.

It’s difficult to refuse to listen despite our best attempts.. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(1). SO! Podcast #82: Living Sounds: Rhythms of Belonging

“CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD: SO! Podcast #82: Living Sounds: Rhythms of Belonging

SUBSCRIBE TO THE SERIES VIA APPLE PODCASTS

FOR TRANSCRIPT: ACCESS EPISODE THROUGH APPLE PODCASTS , locate the episode and click on the three dots to the far right. Click on “view transcript.”

It’s been a minute for the SO! podcast but we are glad to be back–however intermittently–with a podcast episode that shares a discussion between women sound studies artists and scholars. The panel “Living Sounds: Rhythms of Belonging,” was held on September 19 at 6-7pm EDT at The Soil Factory arts space in Ithaca, New York. Moderator Jennifer Lynn Stoever, sound studies scholar and our Ed. in Chief, talks with four women sound artists about their praxis: Marlo de Lara, Bonnie Han Jones, Sarah Nance and Paulina Velazquez Solis.. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

Featured Image: “microphone on the bass drum of the drummer for No Age” by Flickr User Dan MacHold CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2024

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2023!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2020-2022!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2019!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2018!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2017!

The Sounds of Equality: Reciting Resilience, Singing Revolutions

.

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!

When the pandemic hit the world in late 2019, the concept of lockdown ceased the social life of the people and their communities. In these unprecedented circumstances, a video from Italy took the internet. People in Italian towns such as Siena, Benevento, Turin, and Rome were singing from their windows and balconies, which raised morale. The song “Bella Ciao,” an old partisan Italian song, became an anthem of hope against adversity. This anti-fascist song was popularized during the mid-20th century across the globe as a part of progressive movements. Following this, people in many countries around the world created their renditions of “Bella Ciao” in Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish, Persian, French, Spanish, Armenian, German, Portuguese, Russian, and within India in languages such as Punjabi, Marathi, Bangla, and even in sign language renditions. It was such an apt moment that captured the idea of empathy, solidarity, and the human need for community. This moment was still resonating with me when I was approached by Goethe Institut, New Delhi, to work on music and protest, and create The Music Library. I knew what I needed to do.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe Music Library was conceptualized as a weekly playlist of protest songs. I believe protests are not just demands but are aspirations, unfulfilled promises that truly represent the resilience of people. I could not imagine anything more beautiful than protest music to represent the world, as it amplifies human desires for connection and better days ahead. I designed it as a weekly music bulletin that people could dwell in for half an hour, and it would be like a short musical insight to that country or theme. Although the project had to be cut short due to institutional limitations, The Music Library creted 36 weekly playlists focused on liberation movements, anti-colonial struggles, people’s uprisings, and popular expressions of dissent.

The Music Library hosts two types of playlists: issue-based and country- or region-specific. This approach curates and classifies music for a broader audience attuned to these categories. When I prepare a playlist, the first thing I seek is to incorporate marginalized and diverse voices. Diversity can be based on caste, gender, language, region, and more. I typically favor field recordings, amateur productions, and emerging artists. Occasionally, the featured artists have as few as 50 views on their videos. After listening to numerous songs and consulting individuals with greater expertise, I select 5-8 songs and then write a blurb to introduce the playlist. Sometimes, I also seek help for language assistance. In that sense, it’s a very collaborative effort. The Music Library’s mission resonates with Merje Laiapea’s mapping of Ukrainian resistance to the Russian invasion through music. The Music Library similarly engages protest music, but with a wider array of areas and themes.

After the first few weeks, I decided to transition from Indian protest music to global and I wanted to foster a gradual introduction instead of a snap transition. I realized that inviting guest curators would enable the transition to linger on for a bit before settling in, and the guest curators would have a much better idea of the protest culture in their respective country and/or area of research. For example, Sara Kazmi, a scholar-activist-singer from Pakistan, curated a playlist on protest music of Pakistan; Yueng, who is researching Hong Kong music for his Ph.D, curated a playlist on The Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong. So their expertise and knowledge of respective countries give us a better sense of what protest music is for people there than I could provide on my own. Like Sara and Yueng, many of the guest curators have either been part of protest movements or have written, observed, or researched closely. Likewise, there are guest playlists by musicologist Lucas Avidan that emphasize the prominence of hip-hop music, or as some call it “Bonga flava” in Tanzanian protest music, and a playlist on MC Todfod, an emerging rapper from Mumbai Hip-Hop collective Swadesi who passed away at the age of 24. Protests themselves are essentially about bringing people together and working together. In this sense, the co-curatorial process resonated with the idea of protest music itself as a collective action.

The idea of protest is essentially an act, attitude, orientation, and assertion against the dominant conservative system. So, in that sense, its definition is as varied as the kinds of conservatism existing in societies. It could be based on class, caste, gender, race, nation, region, language, food, and culture. In short, protest music means speaking up against power. Protest music plays multiple roles for the people practicing it or whom it represents. In a highly unequal power relationship, it is like a crack or a rupture against hegemony. In others, it asserts power. For many, protest music symbolizes an idea, utopia, like one world or Begumpura, i.e., land without sorrow, in 15th-century saint-poet Ravidas from India. With old social issues such as casteism, patriarchy, feudalism still lingering around and consolidating, and capitalism and nationalism getting strongholds across the globe, the world is more fragmented and hostile. In this situation, the protest music from around the world raises some particular issues but also many universal ones, such as equality, recognition, dignity, food, housing, healthcare, education, and above all, the right to live as an equal citizen. The Music Library brings all of this protest music under a single umbrella, as all this music has one thing in common: Resilience! At times, The Music Library is a music room that soothes, and other times a war cry for equality!

Bangladesh’s playlist, for example, curated by Dhaka-based artist, Emdadul Hoque Topu, is based on Liberation War songs. The Liberation War was a unique liberation movement based on linguistic identity. So, language, a mode of expression like music, was at the heart of the movement. Interestingly, when the recent popular uprising occurred, I was in Dhaka and saw the popular resentment against the Liberation War and its icons. It shows that protest music is as evolving and contemporary as any other expressive form, one age’s protest song could later turn into a voice of the oppressor or used to oppress any dissent. For instance, Rajakars, a term that till recently had very negative connotation due to its association with the detractors of anti-liberation, has been employed and repurposed in a chant or slogan ami ke, tumi ke, Rajakar, Rajakar (who am I, who are you, Rajakar, Rajakar) for the current uprising that led to the overthrow of the Sheikh Hasina-led government.

In another instance, the historic Farmer’s Protest of 2020-21 in India–termed the biggest movement in recorded history– has led to a proliferation of music to bolster it. Though the protest started in the north Indian state of Punjab, it spread across India and drew global support. Punjab is a musically unique place; it is one of India’s most popular and prolific independent music industries. Due to early migration history, Punjabi music has spread globally and has been adaptive of derived from various musical cultures such as rap, pop, etc, while maintaining its distinct linguistic identity. This made the Punjabi music popular and relevant beyond its linguistic boundaries. The movement has been chronicled by a newsletter called the Trolley Times, where I worked as a co-editor. Numerous Punjabi singers have contributed immensely by producing music and being part of the movement. After a long time, a strong impulse in the popular cultural sphere evolved in solidarity with the mass movement.

The Music Library was under construction when the world was going through a pandemic, and unprecedented isolation, a hallmark of oppression. In the pandemic, when people were dying, this quote became popular: Corona is the virus, Capitalism is the pandemic. People could see the havoc of capitalism playing out in full public display from the first world to the third world. Someone who is cornered, pushed against the wall, with no recourse to grievance redressal, cries out to make themselves count, and find solidarity and rise. I designed The Music Library to show how music can break a slumber and bring people to march together, similarly to what “Bella Ciao” did during COVID-19.

It began as a hum that was joined by neighbors, and then it spread, loudly, across the world as an expression of solidarity and resilience. “Bella Ciao” is such a marvellous testimony of what music can do and has been doing! I hope The Music Library serves as a humble repository of this resilience.

—

Featured Image: Image of “Bella Ciao” being sung in Santiago, Chile during the ‘estallido social’ (2019) by AbarcaVasti, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

—

Mukesh Kulriya is a Ph.D. scholar in Ethnomusicology at The Herb Alpert School of Music, University of California, Los Angeles, USA. His research focuses on the intersection of music and religion in South Asia in the context of gender and caste. His Ph.D. research examines bhakti, or devotion practices within the ambit of popular religion in Rajasthan, India. Since 2010, he has collaborated on India-based projects centered around the craft, culture, folk music, and oral traditions as an organizer, archivist, translator, and researcher. He also works on global protest music and currently working on a podcast on Music and Hate.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Twitchy Ears: A Document of Protest Sound at a Distance–Ben Tausig

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom – Carter Mathes

#MMLPQTP Politics: Soccer Chants, Viral Memes, and Argentina’s 2018 “Hit of the Summer”–Michael S. O’Brien

A Tradition of Free and Odious Utterance: Free Speech & Sacred Noise in Steve Waters’s Temple–Gabriel Salomon Mindel and Alexander J. Ullman

Singing The Resistance: January 2017’s Anti-Trump Music Videos–Holger Schulze

Recent Comments