Ronca Realness: Voices that Sound the Sucia Body

This series listens to the political, gendered, queer(ed), racial engagements and class entanglements involved in proclaiming out loud: La-TIN-x. ChI-ca-NA. La-TI-ne. ChI-ca-n-@. Xi-can-x. Funded by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation as part of the Crossing Latinidades Humanities Research Initiative, the Latinx Sound Cultures Studies Working Group critically considers the role of sound and listening in our formation as political subjects. Through both a comparative and cross-regional lens, we invite Latinx Sound Scholars to join us as we dialogue about our place within the larger fields of Chicanx/Latinx Studies and Sound Studies. We are delighted to publish our initial musings with Sounding Out!, a forum that has long prioritized sound from a queered, racial, working-class and “always-from-below” epistemological standpoint. —Ed. Dolores Inés Casillas

—

My Puerto Rican grandmother used to sing Pedro Infante’s “Las mañanitas” to all the women in the family on their birthdays, so naturally I grew up thinking this was a Puerto Rican song. Not quite – it’s Mexican. When my family came to New York City from Puerto Rico in the 1950s, they were starved of warm waters, mountains, and family members, but they were not starved of Spanish-language music and media thanks in large part to Mexico’s Golden Age of Cinema. In the Bronx, Puerto Ricans would go the theaters to watch movies like Nosotros los Pobres (1948),which popularized boleros like “Las Mañanitas.” This movie-going ritual in the wake of relocation and diaspora has provided the birthday soundtrack to my life.

My mother grew up listening to her father sing boleros, and she would later sing with the Florida Grand Opera Chorus when I was a child. My early knowledge of opera came from her. Growing up in Miami Beach, I would also listen to reggaetón and hip-hop in afterschool programs. The Parks & Recreation department would host dances for us, and that was where I first learned to dance perreo. My early musical surroundings represent what it means to be a colonial subject, to hear the Italianate vocal legacies of opera mixed with the Afro-Diasporic and Indigenous rhythms of reggaetón. This post contextualizes my experience within bolero’s colonial history and legacy particularly its operatic disciplining of brown and Black bodies and voices. Reggaetóneras provide models for sonic subversion by being ronca, raspy, or breathy, and thus overriding internalized Eurocentric dichotomies of feminine and masculine vocal timbres.

When I began my own operatic training in college, I was constantly told to “purify” my voice, to resist vocal “fry,” and to handle my acid reflux by avoiding spicy foods. I was steered away from singing the pop songs I had grown up with, and kept many musical activities secret, like when I soloed for the tango ensemble and my a cappella group. In graduate school, thanks to my Latina roommates, I began listening to reggaetón again. I reunited with the voices that raised me and was reassured that their teachings of resistance would always present themselves when I needed them.

After 20 years of listening to Ivy, I have located the descriptor that most closely encapsulates the way her voice sounds to me: ronca. This is Spanish for hoarse, and in my experience, it’s been used colloquially, mostly by women, to describe moments when their throats might feel sore, and their voices sound raspy, or masculine, even. Ronca has been articulated as an epistemology of vocal sounding in the artistry of lower-class Black reggaetón creators like Don Omar and more recently, Ozuna. Sounding ronca is a signifier of realness, of truly knowing the struggle of race and class oppression. It is a vocalization of full-body rage fueled by poverty and colonization.

Ivy’s voice is so special to me because she sounds like my aunt when she’s had a long day, my mom when she’s yelling, and my grandma after years of having long days and yelling at people. She sounds like the raw, unfiltered power that comes from exhaustion. She sounds like inner will and justified fury. She sounds like yelling at landlords and ex-husbands for hot water and child support. She sounds like age. And she always has, even when she was “young.” And this sound is even more beautiful and life-giving to me after 4+ years in a classical voice program that told me it was bad to sound hoarse or raspy, surveilled my eating, and perpetuated the colonization of Native and Black peoples through musical subjugation.

Operatic training utilizes mechanisms that are opposite of what is “natural” for me as a poor Latina from the barrio. It asks me to lift my voice, clarify it, and feminize it. This, to me, is antithetical to the girl who laughs really loudly, gets raspy often from yelling and eating too many Takis, and loves to sing from her chest. Ivy’s voice empowers my place as the antithesis. Even as I sang classically in college, my voice was still often described as “soulful,” “hoarse,” “raspy,” “throaty.” My voice, although in a moment of attempted cleanup in college, was read as having previously engaged in genres that disrupt colonial dichotomies of “art” and “noise.” The sonic Blackness– in particular the exoticized and tropicalized Blackness of Latinidad in the U.S.- of my timbre was legible, and perhaps even hyper-audible, in moments when I was trying to adapt to European art forms. Raquel Z. Rivera asserts in New York Ricans from the Hip Hop Zone (2003) that Latinidad doesn’t take away from Blackness but adds an element of exoticism to the Blackness. Thus, I have come to understand ronca voices as representative of a Latina/e liberatory sonic and embodied praxis that resists the derogatory discourse around racialized voices predicated on European ideals of cleanliness.

The ronca voice is negotiating suciedad, Deborah Vargas’ analytic for how queers of color may reclaim their abject bodies and social spaces. Readings of my voice in predominantly white spaces were contextualized by my queer ambiguously-brown body, which in direct opposition to whitening regimes, was sounding suciedad. This is what ronca voices do, and what I conceptualize as “ronca realness”: the tendency of Latinas/es to not hide behind the voice but rather keep it real with the audience via their vocal timbre. Ronca voices sound another option to Barthes’ hegemonic article “The Grain of the Voice,” which has been applied to Ivy Queen and Don Omar in Jennifer Domino Rudolph’s “‘Roncamos Porque Podemos,’” and Dara Goldman’s “Walk like a Woman, Talk like a Man: Ivy Queen’s Troubling of Gender.” I intend ronca realness to be understood as a queer of color vocal analytic born from community and lived experience.

Ronca voices reflect emotional states, flip colonial gendered vocal scripts, reveal if the singer had coffee that morning and Hot Cheetos the night before, and navigate tough musical contours with strain and stress; most importantly, they refuse to be white(ned). In college, my ronca realness was not always a choice. Keeping it real, in general, is sometimes undecided upon prior to the act of realness; it is an additional and deeply engrained responsibility that queer people of color have in white spaces to sound their dissent, or else face the continued exploitation of their communities. Further, these acts of realness may not even be legible as such but are often coded as bad behavior or an attitude problem.

Within communities of color and (im)migrant communities, it’s important to recognize that Ivy Queen’s ronca timbre was permissible because she was light-skinned, thin, and usually took on the masculine role of the rapper, rather than the feminine role of the dancer, in several of her videos. These privileges have left Afro-Latina ronca reggaetóneras like La Sista in the shadows.

La Sista has veered away from sounding ronca in recent years, but in her debut album, Majestad Negroide (2006), she praised Yoruba goddess Yemaya and Taino cacique Anacaona with a hoarse, raspy, bold sound. She is the Afro-Indigenous Latina many of us needed growing up, and her absence speaks to the ways in which Black ronca voices are policed and erased within Latinx culture and elsewhere. Let us praise her now.

—

Featured Image: Still image by SO! from RaiNao’s “Tentretiene”

—

Cloe Gentile Reyes (she/her) is a queer Boricua scholar, poet, and performer from Miami Beach. She is a soon-to-be Faculty Fellow in NYU’s Department of Music and earned her PhD in Musicology from UC Santa Barbara. Her writing explores how Caribbean femmes navigate intergenerational trauma and healing through decolonial sound, fashion, and dance. Cloe’s poems have been featured in the womanist magazine, Brown Sugar Lit, and she has presented and performed at PopCon, Society for American Music, International Association for the Study of Popular Music-US Branch, among several others.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Contra La Pared: Reggaetón and Dissonance in Naarm, Melbourne—Lucreccia Quintanilla

“How Many Latinos are in this Motherfucking House?”: DJ Irene, Sonic Interpellations of Dissent and Queer Latinidad in ’90s Los Angeles—Eddy Francisco Alvarez Jr.

Unapologetic Paisa Chingona-ness: Listening to Fans’ Sonic Identities–Yessica Garcia Hernandez

SO! Podcast #74: Bonus Track for Spanish Rap & Sound Studies Forum

Cardi B: Bringing the Cold and Sexy to Hip Hop—Ashley Luthers

The Cyborg’s Prosody, or Speech AI and the Displacement of Feeling

In summer 2021, sound artist, engineer, musician, and educator Johann Diedrick convened a panel at the intersection of racial bias, listening, and AI technology at Pioneerworks in Brooklyn, NY. Diedrick, 2021 Mozilla Creative Media award recipient and creator of such works as Dark Matters, is currently working on identifying the origins of racial bias in voice interface systems. Dark Matters, according to Squeaky Wheel, “exposes the absence of Black speech in the datasets used to train voice interface systems in consumer artificial intelligence products such as Alexa and Siri. Utilizing 3D modeling, sound, and storytelling, the project challenges our communities to grapple with racism and inequity through speech and the spoken word, and how AI systems underserve Black communities.” And now, he’s working with SO! as guest editor for this series (along with ed-in-chief JS!). It kicked off with Amina Abbas-Nazari’s post, helping us to understand how Speech AI systems operate from a very limiting set of assumptions about the human voice. Then, Golden Owens took a deep historical dive into the racialized sound of servitude in America and how this impacts Intelligent Virtual Assistants. Last week, Michelle Pfeifer explored how some nations are attempting to draw sonic borders, despite the fact that voices are not passports. Today, Dorothy R. Santos wraps up the series with a meditation on what we lose due to the intensified surveilling, tracking, and modulation of our voices. [To read the full series, click here] –JS

—

In 2010, science fiction writer Charles Yu wrote a story titled “Standard Loneliness Package,” where emotions are outsourced to another human being. While Yu’s story is a literal depiction, albeit fictitious, of what might be entailed and the considerations that need to be made of emotional labor, it was published a year prior to Apple introducing Siri as its official voice assistant for the iPhone. Humans are not meant to be viewed as a type of technology, yet capitalist and neoliberal logics continue to turn to technology as a solution to erase or filter what is least desirable even if that means the literal modification of voice, accent, and language. What do these actions do to the body at risk of severe fragmentation and compartmentalization?

I weep.

I wail.

I gnash my teeth.

Underneath it all, I am smiling. I am giggling.

I am at a funeral. My client’s heart aches, and inside of it is my heart, not aching, the opposite of aching—doing that, whatever it is.

Charles Yu, “Standard Loneliness Package,” Lightspeed: Science Fiction & Fantasy, November 2010

Yu sets the scene by providing specific examples of feelings of pain and loss that might be handed off to an agent who absorbs the feelings. He shows us, in one way, what a world might look and feel like if we were to go to the extreme of eradicating and off loading our most vulnerable moments to an agent or technician meant to take on this labor. Although written well over a decade ago, its prescient take on the future of feelings wasn’t too far off from where we find ourselves in 2023. How does the voice play into these connections between Yu’s story and what we’re facing in the technological age of voice recognition, speech synthesis, and assistive technologies? How might we re-imagine having the choice to displace our burdens onto another being or entity? Taking a cue from Yu’s story, technologies are being created that pull at the heartstrings of our memories and nostalgia. Yet what happens when we are thrust into a perpetual state of grieving and loss?

Humans are made to forget. Unlike a computer, we are fed information required for our survival. When it comes to language and expression, it is often a stochastic process of figuring out for whom we speak and who is on the receiving end of our communication and speech. Artist and scholar Fabiola Hanna believes polyvocality necessitates an active and engaged listener, which then produces our memories. Machines have become the listeners to our sonic landscapes as well as capturers, surveyors, and documents of our utterances.

The past few years may have been a remarkable advancement in voice tech with companies such as Amazon and Sanas AI, a voice recognition platform that allows a user to apply a vocal filter onto any human voice, with a discernible accent, that transforms the speech into Standard American English. Yet their hopes for accent elimination and voice mimicry foreshadow a future of design without justice and software development sans cultural and societal considerations, something I work through in my artwork in progress, The Cyborg’s Prosody (2022-present).

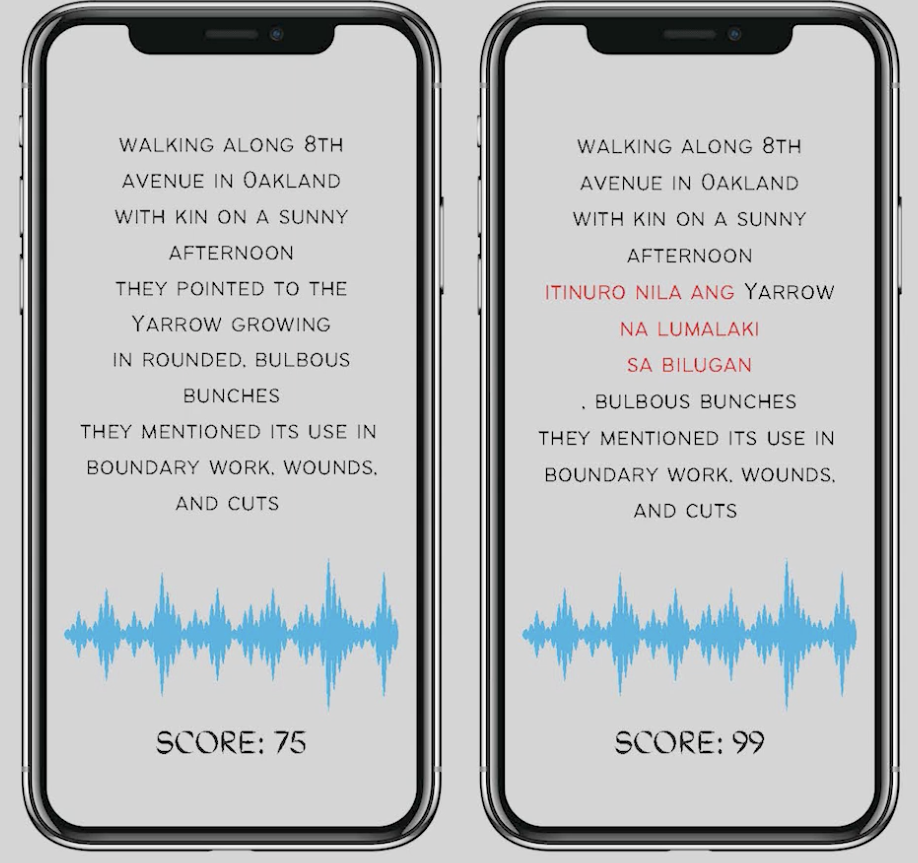

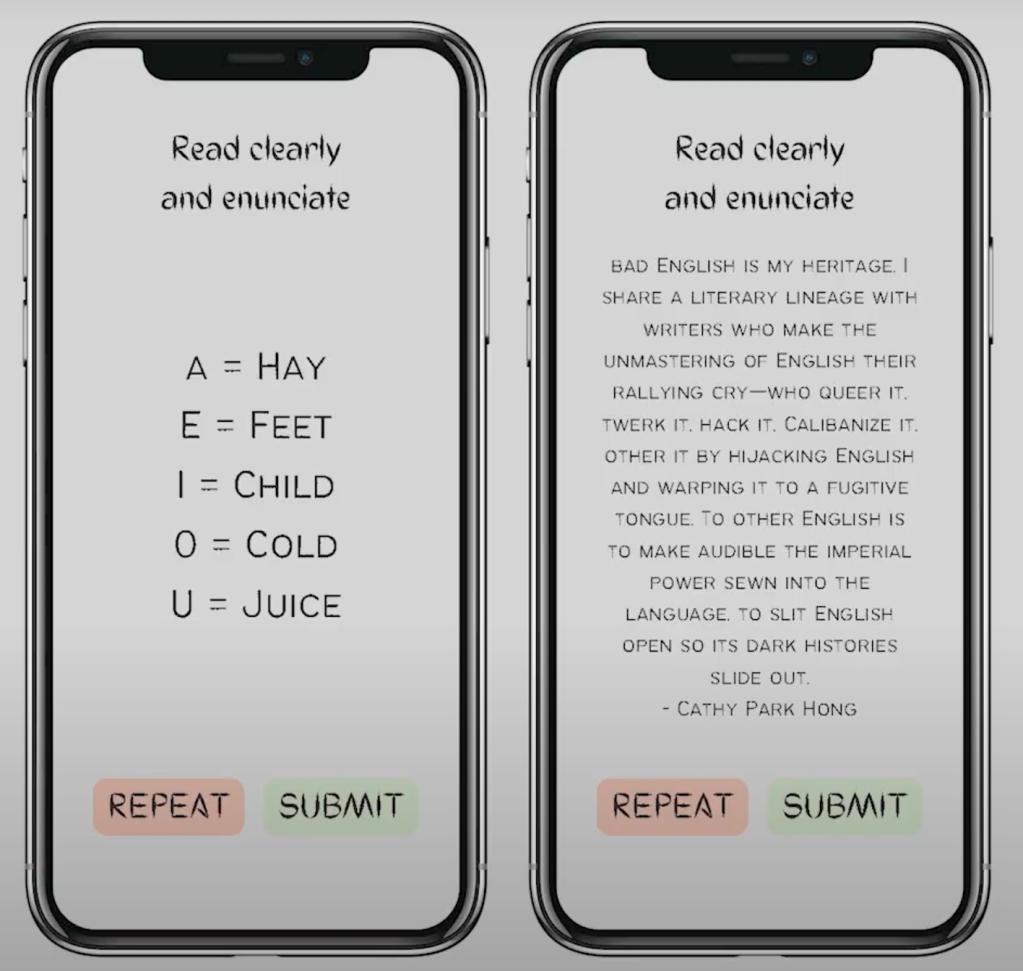

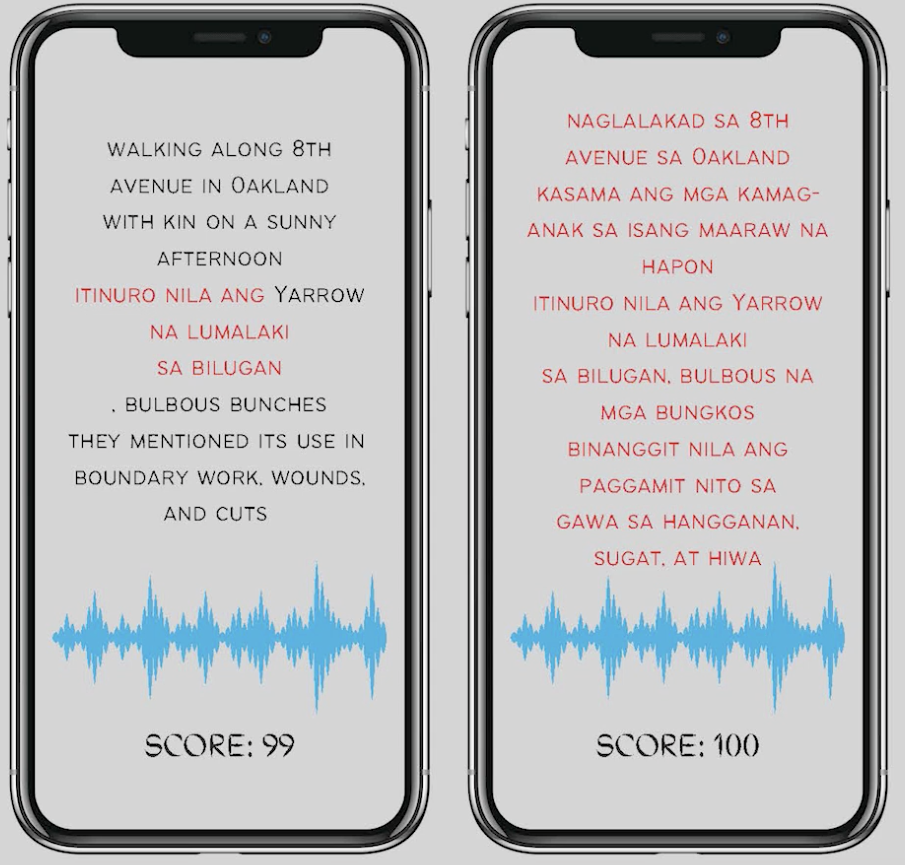

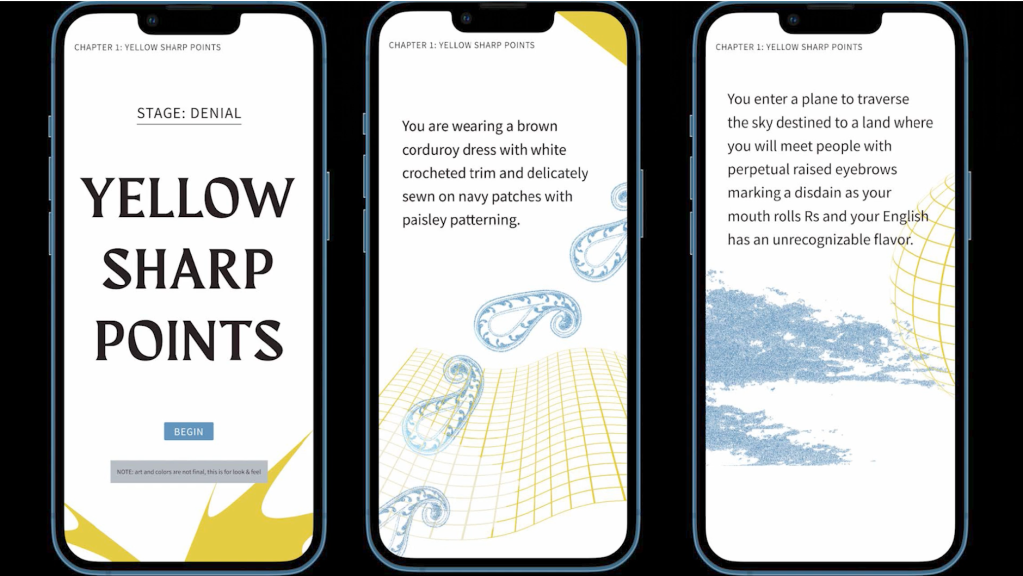

The Cyborg’s Prosody is an interactive web-based artwork (optimized for mobile) that requires participants to read five vignettes that increasingly incorporate Tagalog words and phrases that must be repeated by the player. The work serves as a type of parody, as an “accent induction school” — providing a decolonial method of exploring how language and accents are learned and preserved. The work is a response to the creation of accent reduction schools and coaches in the Philippines. Originally, the work was meant to be a satire and parody of these types of services, but shifted into a docu-poetic work of my mother’s immigration story and learning and becoming fluent in American English.

Even though English is a compulsory language in the Philippines, it is a language learned within the parameters of an educational institution and not common speech outside of schools and businesses. From the call center agents hired at Vox Elite, a BPO company based in the Philippines, to a Filipino immigrant navigating her way through a new environment, the embodiment of language became apparent throughout the stages of research and the creative interventions of the past few years.

In Fall 2022, I gave an artist talk about The Cyborg’s Prosody to a room of predominantly older, white, cisgender male engineers and computer scientists. Apparently, my work caused a stir in one of the conversations between a small group of attendees. A couple of the engineers chose to not address me directly, but I overheard a debate between guests with one of the engineers asking, “What is her project supposed to teach me about prosody? What does mimicking her mom teach me?” He became offended by the prospect of a work that de-centered his language, accent, and what was most familiar to him.The Cyborg’s Prosody is a reversal of what is perceived as a foreign accented voice in the United States into a performance for both the cyborg and the player. I introduce the term western vocal drag to convey the caricature of gender through drag performance, which is apropos and akin to the vocal affect many non-western speakers effectuate in their speech.

The concept of western vocal drag became a way for me to understand and contemplate the ways that language becomes performative through its embodiment. Whether it is learning American vernacular to the complex tenses that give meaning to speech acts, there is always a failure or queering of language when a particular affect and accent is emphasized in one’s speech. The delivery of speech acts is contingent upon setting, cultural context, and whether or not there is a type of transaction occurring between the speaker and listener. In terms of enhancement of speech and accent to conform to a dominant language in the workplace and in relation to global linguistic capitalism, scholar Vijay A. Ramjattan states in that there is no such thing as accent elimination or even reduction. Rather, an accent is modified. The stakes are high when taking into consideration the marketing and branding of software such as Sanas AI that proposes an erasure of non-dominant foreign accented voices.

The biggest fear related to the use of artificial intelligence within voice recognition and speech technologies is the return to a Standard American English (and accent) preferred by a general public that ceases to address, acknowledge, and care about linguistic diversity and inclusion. The technology itself has been marketed as a way for corporations and the BPO companies they hire to mind the mental health of the call center agents subjected to racism and xenophobia just by the mere sound of their voice and accent. The challenge, moving forward, is reversing the need to serve the western world.

A transorality or vocality presents itself when thinking about scholar April Baker-Bell’s work Black Linguistic Consciousness. When Black youth are taught and required to speak with what is considered Standard American English, this presents a type of disciplining that perpetuates raciolinguistic ideologies of what is acceptable speech. Baker-Bell focuses on an antiracist linguistic pedagogy where Black youth are encouraged to express themselves as a shift towards understanding linguistic bias. Deeply inspired by her scholarship, I started to wonder about the process for working on how to begin framing language learning in terms of a multi-consciousness that includes cultural context and affect as a way to bridge gaps in understanding.

Or, let’s re-think this concept or idea that a bad version of English exists. As Cathy Park Hong brilliantly states, “Bad English is my heritage…To other English is to make audible the imperial power sewn into the language, to slit English open so its dark histories slide out.” It is necessary for us all to reconfigure our perceptions of how we listen and communicate that perpetuates seeking familiarity and agreement, but encourages respecting and honoring our differences.

—

Featured Image: Still from artist’s mock-up of The Cyborg’s Prosody(2022-present), copyright Dorothy R. Santos

—

Dorothy R. Santos, Ph.D. (she/they) is a Filipino American storyteller, poet, artist, and scholar whose academic and research interests include feminist media histories, critical medical anthropology, computational media, technology, race, and ethics. She has her Ph.D. in Film and Digital Media with a designated emphasis in Computational Media from the University of California, Santa Cruz and was a Eugene V. Cota-Robles fellow. She received her Master’s degree in Visual and Critical Studies at the California College of the Arts and holds Bachelor’s degrees in Philosophy and Psychology from the University of San Francisco. Her work has been exhibited at Ars Electronica, Rewire Festival, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and the GLBT Historical Society.

Her writing appears in art21, Art in America, Ars Technica, Hyperallergic, Rhizome, Slate, and Vice Motherboard. Her essay “Materiality to Machines: Manufacturing the Organic and Hypotheses for Future Imaginings,” was published in The Routledge Companion to Biology in Art and Architecture. She is a co-founder of REFRESH, a politically-engaged art and curatorial collective and serves as a member of the Board of Directors for the Processing Foundation. In 2022, she received the Mozilla Creative Media Award for her interactive, docu-poetics work The Cyborg’s Prosody (2022). She serves as an advisory board member for POWRPLNT, slash arts, and House of Alegria.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Your Voice is (Not) Your Passport—Michelle Pfeifer

“Hey Google, Talk Like Issa”: Black Voiced Digital Assistants and the Reshaping of Racial Labor–Golden Owens

Beyond the Every Day: Vocal Potential in AI Mediated Communication –Amina Abbas-Nazari

Voice as Ecology: Voice Donation, Materiality, Identity–Steph Ceraso

The Sound of What Becomes Possible: Language Politics and Jesse Chun’s 술래 SULLAE (2020)—Casey Mecija

Look Who’s Talking, Y’all: Dr. Phil, Vocal Accent and the Politics of Sounding White–Christie Zwahlen

Listening to Modern Family’s Accent–Inés Casillas and Sebastian Ferrada

Recent Comments