Mapping the Music in Ukraine’s Resistance to the 2022 Russian Invasion

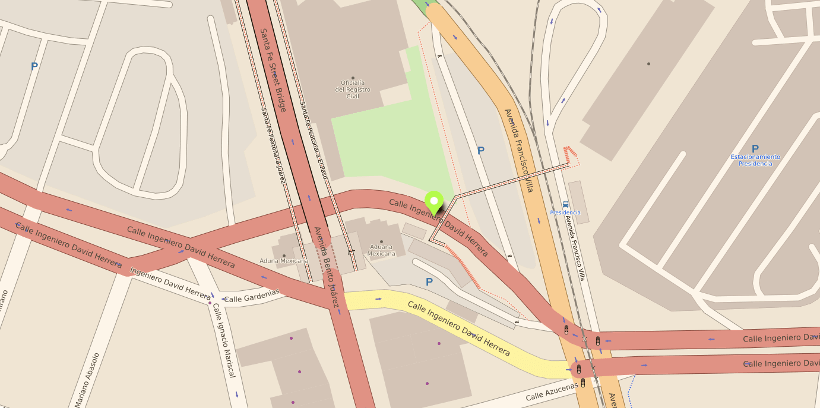

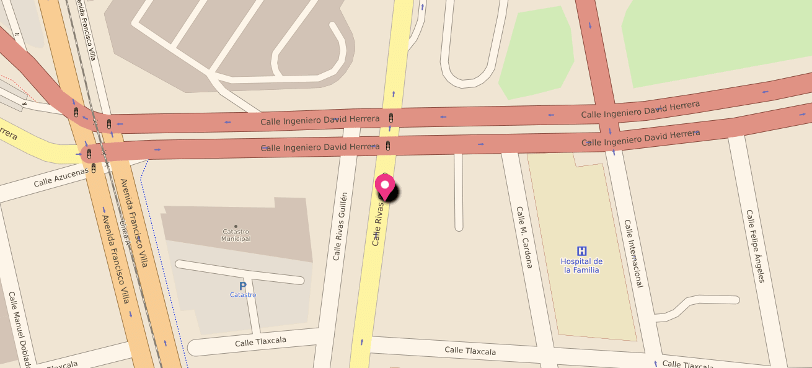

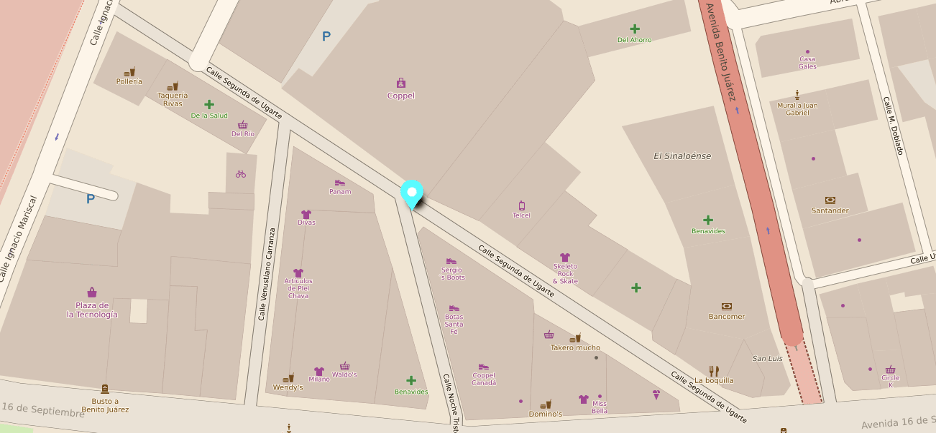

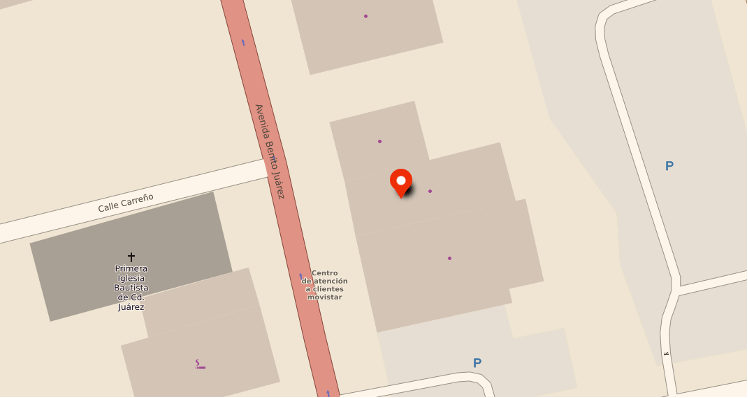

Note: To see these tweets and videos embedded on an interactive map, click here.

In the late morning of February 24th, 2022, an American journalist captured a young boy on the grand piano in Kharkiv Palace Hotel playing Philip Glass’s composition ‘Walk to School’. The city of Kharkiv was the first in Ukraine to wake up to missile strikes that very morning – the first day of Russia’s full invasion. It is a child’s peaceful reaction to violent intentions. The conflicting feelings evoked by this one scene alone, while the Russian army was advancing on the city, are powerful. It also became an example of a filmed musical event that gained viral international attention through social media and evoked an expression of solidarity from the song’s authors.

The city of Kharkiv was a key site of Stalin’s ‘brotherly terrors’ in the 1930s, most well-known of which is the Holodomor Famine Genocide of 1932-33, when approximately 4 million people died. As part of cultural ethnic cleansing, countless Ukrainian intellectuals in literature, theatre, arts, and music were killed. Soviet authorities exterminated hundreds of kobzars in Kharkiv, the wandering and often blind minstrels of Ukraine. Invited under the pretense of attending a musicians’ convention in 1932, notes Viktor Mishalow in his 2008 dissertation “Cultural and Artistic Aspects of the Origins and Development of the Kharkiv Bandura,” the kobzars and the ethnomusicologists who researched and documented their music, were executed.

Stalin’s violent transformation of the rural society essentially ended the kobzardom, and performing on the lute-like instrument kobza was replaced with performances of folk and classical music on the bandura – in an attempt to re-territorialise the tradition. As Ian Biddle and Vanessa Knights (2018) argue, ‘the re-territorialisation of local heterogeneous musics to nationalist ends has often signalled the death or near-fatal displacement of regional identities’ (12). These new performances consisted of censored versions of traditional kobzar repertoire and focused on stylised works that praised the Soviet system. As in all occupied regions, the Soviet authorities had identified a music which carried a strong national sentiment and attempted to change its meaning, an example of how musical styles can be made emblematic of national identities in contradictory ways (Stokes 2014).

In addition to being a centre for classical music, the multicultural city of Kharkiv is considered the country’s capital of hip hop, a genre that Helbig (2014) argues that in Ukraine ‘oscillates between the highly politicised and the farcical.’ Throughout the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union the Ukrainian language was suppressed, and the decision to rap in Russian or Ukrainian, continues to politicise the genre. The Russian language opens up a bigger market for artists, but Ukrainian carries a strong national sentiment, especially in light of progress by national leaders such as Yushchenko and Zelenskyy in bringing awareness to the violent events in the region’s history. Interestingly, the most famous Kharkiv group TNMK (Tanok na Maidani Kongo) rap in Ukrainian and interject their lyrics with surzhyk, a creole mix of Ukrainian and Russian typical of eastern Ukraine (Bilaniuk 2006).

Fierce political meanings in Ukrainian hip hop are exemplified by the song most associated with the Orange Revolution – rapper GreenJolly’s ‘Together we are many, we will not be defeated’. Ukrainian lyrics index the communal force of approximately half of the country’s population that opposed the fraudulent presidential election results Helbig (2014). Recorded in four hours, the song embodies the fight against lies, corruption and censorship. The Orange Revolution achieved its re-election goal through peaceful means, and musically it marked a victory for Ukrainian-language songs, especially rock and hip-hop, over Soviet-style and commercial Russian-language pop associated with the Yanukovych campaign, argues Klid (2007, 131).

It is no surprise then, that on February 25th, 2022, a day after Russian invasion, a video emerged of Kyiv university students hiding from shelling singing along to ’22’ by Ukrainian rapper Yarmak. This political hip hop song had soundtracked the later and more serious stage of the Euromaidan, with its title referring to the number of years Ukraine had been independent from the USSR at the time. The lyrics speak of an exploited and beaten 22-year-old girl whose name is ‘Ukraine’, poignant for the later stage of the uprising when police brutality had turned the peaceful protests into deadly street battles (Hansen 2019). Here, the language of music is directly informed by the metaphors of conflict, offering in turn a ‘lexical setting’ for understanding the place of music in it (O’Connell 2010).

Hip hop has gained popularity since the early 90s, a phenomenon which has been attributed to the wider embrace of Western musics and the English language, the ‘cool’ element of the genre as an identity marker for young people signalling connections to the West, and, in part, to how Black expressive culture has the ability to connect with other scenes of resistance, displacement and exclusion: Jewish and Asian, to name a few (Melnick 1999, Wong 2004). Hip hop in Ukraine has become a space in which to negotiate a cultural identity, the revival of the ‘local’ and the influence of the global, the Western cultural space and the lived Soviet history; the shift in the Ukrainian consciousness towards the West, and the long-term effects of Russification.

As such, hip hop in Ukraine takes on interesting aesthetic qualities, resulting in the ‘angry folk rap’ (Hansen 2019) of the Dakh Daughters, or The Kalush Orchestra, the folk rap group representing Ukraine in the 2022 Eurovision Song Contest. After taking up arms as part of the Territorial Defense of Kyiv or supporting humanitarian efforts during the first month of the war, The Kalush Orchestra were seen on the streets of Lviv again on April 2nd performing their winning entry ‘Stefania’.

The song – written for the frontman Oleh Psiuk’s mother – now an ode to all Ukrainian mothers – could be viewed as a utopian space in which regional, national and other ideological affiliations are levelled out ( Biddle and Knights, 2008). The group’s folk-rap song ‘Stefania’ utilises the Ukrainian woodwind instrument of the flute family called Sopilka, in a similar way that singer Ruslana featured the Trembitas – Ukrainian wooden alpine horns – in her winning entry back in 2004.

Ukraine’s music scene is a site of identity discourse to locate a certain kind of ‘rootedness’ in linguistics and folklore – a territorial, inward-looking sense of place (Nederveen Pieterse 1995: 61). The presence of folk elements in contemporary composition reflects a strong ethnomusicological revival, as students and scholars have travelled to rural areas to record the surviving musics. The relationship between musical materials and the sonic projection of territory is complex, and such mixed genres should not be articulated simply as examples of musical hybridity. In Ukraine, they seem to conjure up a liminal ‘interspace’ between a historicised imagination of Ukrainian folk and the hip hop sensibility, where the encounter between folk and hip hop is a meeting of the regional and the global, the latter always ready to absorb and redistribute the former (Biddle and Knights, 2008, 13).

For an oppressive power imposing cultural hegemony by force, a folk song with its deep histories and meanings is dangerous, best felt through this video of Katya Chilly performing ‘The Willow Board’ in Kyiv.

I saw Ukrainian folk music legend Katya Chilly today! Here she is, singing barefoot in Kyiv. Not besieged,not encircled Kyiv. Calm and polite Kyiv, waiting and getting ready for everything pic.twitter.com/4RI51DjlQY

— Nika Melkozerova (@NikaMelkozerova) March 19, 2022

This folk song was traditionally performed while playing a spring game and gained popularity through the Ukrainian film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors from 1965. The film is a masterpiece of Ukraine’s cinematic history and tells the story of Ukrainian Hutsul lovers in the Carpathian mountains. Back in the 60s, Soviet reviewers departed from international acclaim and criticised the film’s fascination with Ukrainian ancestry, as well as its departure from socialist realism – the official genre in the USSR (Boboshko, 1964). Ukrainian history is punctuated by such subversive cultural products, from the songs created by Ukrainian Sich Riflemen during WW1, or the performance of bard music as protest and dissent in the 60s and 70s. In the 1980s, Glasnost and the weakened state of the Soviet Union allowed for the Ukrainian bandura, and surviving kobzas, to be played in public again alongside Western genres, such as rock and electronic – music scenes that balanced themselves on the Westernmost margins of permitted Soviet culture (Smidchens 2014, 209).

One of the most circulated videos of the 2022 invasion is a video of Andriy Khlyvniuk, member of funk-rap group Boombox, performing a song written in 1914 in memory of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen.

This dude is #Ukraine’s most popular hiphop singer. Also immensely popular in #Russia. This is how he spends his days now: pic.twitter.com/Dm4aZlQjXD

— UkraineStream 🇺🇦 (@ukrainestream) February 28, 2022

‘The Red Viburnum In The Meadow’ represents the national kalyna fruit of Ukraine and implies a connection to blood roots and an ancestral homeland. First remixed by South African artist Kiffness, the video achieved its highest recognition after Pink Floyd featured Khlyvniuk’s vocals in their first release in thirty years, significant to those who remember the rock and roll resistance movements in Eastern Europe which, in the 1970s-80s, formulated a critique of society that ‘literally made the regime face the music’ (Risch 2014, 245).

Because music-making is associated strongly with celebratory occasions, many artists ceased performing and recording as usual, and either enlisted or applied their talents to humanitarian effort. Folk musician Taras Kompanichenko enlisted in the defence forces and was seen performing his kobza to fellow troops.

Okean El’zy’s frontman Svyatoslav Vakarchuk continued to lift the spirits of people hiding in metro stations as these transformed into important sites of musical activity. After three days spent underground, violin student Masha Zhuravlyova picked up her instrument, and through personal expression, helped release stress in the people and pets around her. The thread here is of music as survival, and music as a resource for emotional solidarity in communities that have been subjected to extremes of violence (Stokes 2020). Masha inspired her teacher, violinist Vera Lytovchenko, to perform a 19th century folk song ‘What a Moonlit Night’ in what became a widely circulated video from a Kharkiv shelter. In this rare video from Mariupol where the Russian military hit hardest, newborn baby Nikitos was sang to by her mother in a shelter.

Imagine giving birth in sieged Mariupol, under constant bombardment. Imagine singing to your newborn like this in a bomb shelter. Imagine escaping the blockaded city with him in your arms, risking your life at every single step. Ukrainians don’t have to imagine. This is our life. pic.twitter.com/NqOsROwL2b

— Anastasiia Lapatina (@lapatina_) April 5, 2022

On the whole, the song that has appeared most in this resistance, is the Ukrainian anthem. It appeared in high numbers from the very first days of the invasion; in Kyiv, to help cope with the initial shock and violence of war; or in Mariupol, where a teenager prepared for what was to come.

While the Russians continue to advance on the strategic port city, of Mariupol, I end today‘s Twitter flood with this beautiful video of a teenager singing the 🇺🇦 anthem on the Freedom Square of Mariupol. He sang there during an air raid. The voice of freedom will prevail ✊🏻 pic.twitter.com/LvJfo3gmlW

— Mattia Nelles (@mattia_n) February 27, 2022

In Sumy, the anthem was played out of a window on trumpet after fierce street battles; an act of collective feeling that resulted in pro-Ukraine chants from neighbours, and example of how ’tuning in’ (Schütz 1977) through music can lead to a powerful affective experience that literally embodies social identity (Stokes 2014, 12). The anthem was performed on a daily basis by the Odesa opera singers while filling sand bags on the beach, and repeatedly used in radio warfare to jam Russian military communications.

Au yacht club d’Odessa, les chanteurs d’opéra Yuriy Dudar et Andrey Harlaov sont venus remplir des sacs de sable. Ils font de temps en temps des pauses pour chanter l’hymne national ukrainien pic.twitter.com/PJ76C0ndsZ

— Pierre Alonso (@pierre_alonso) March 8, 2022

The Ukrainian anthem is called ‘Ukraine is Not Yet Dead’, composed in 1863 by Mykhailo Verbytsky to a patriotic poem by ethnographer Pavlo Chubynsky. It was the short-lived anthem of the Ukrainian National Republic in 1917 and restored as such after the restoration of independence in 1992. As it represents both national feeling and a long struggle for autonomy from Russia, it was significant to see it performed by an anti-war protester in Moscow, who was detained as a result.

#Russia More than 2000 people have been detained in Russia during anti-war protests. This is Moscow. This man is singing the state anthem of #Ukraine pic.twitter.com/4rndvpdK2v

— Hanna Liubakova (@HannaLiubakova) March 6, 2022

Most interestingly, across Ukraine, the anthem was performed in collective singing sessions next to tanks or in attempts to stop them. Music became the means by which the community appeared as such to itself, and also the means by which it projected itself to the Russian soldiers (Stokes 2014, 12). In the region of Melitopol, one of the first to be captured by Russian forces, civilians gathered to protest the occupation, and, using the anthem as their weapon, successfully made a Russian convoy turn around. As the singing continued on a daily basis, there is a high number of video evidence online, including this clip which captures a protester’s conversation with a Russian soldier. In what some commentators have concluded as an ‘uncomfortable’ exchange for the soldier, the woman says: ’You see we are just regular people? We are not ‘banderas’. Some of my family lives near Moscow’. Near Energodar, one such confrontation turned violent. A group of civilians sang the anthem near a Russian column and the armed troops responded by throwing grenades (trigger warning: violence). In this instance, the music emanating from civilian bodies became a direct target in warfare.

Ordinary people. These amazing, wonderful, unbreakable people who are changing history in Ukraine.

Here they are – singing Ukrainian anthem in the occupied Berdyansk. #StandWithUkraine#visamastercardleaverussia pic.twitter.com/EQcldgqacc— olexander scherba🇺🇦 (@olex_scherba) February 28, 2022

Civilians in occupied towns kept coming together to sing in what Benedict Anderson calls a ‘unisonance,’ a ‘physical realisation of the imagined community’ (Smidchens 2014, 78; Anderson 1991). Signs of musical identity organise strategic, intersectional mobilisations of community around struggles for social and political justice, argues Stokes (2014). Of key interest is this battle of anthems in Kherson on March 20th. In a physical manifestation of the ‘patriotic myth’ (Sugarman 2010) that romanticises the Soviet Union and informs the violent effort to rebuild it, Russian soldiers blasted the USSR anthem from one side of the street, while local groups resisted by singing the Ukrainian anthem on the other.

Occupied #Kherson. Invaders play back the anthem of USSR. Locals sing the anthem of #Ukraine.#StandWithUkraine️ #UkraineUnderAttack #RussiaInvadedUkraine #Terrorussia #PutinIsaWarCriminal #StopPutin #RussianUkrainianWar #RussiaGoHome #НетВойнe #россиясмотри #Russia pic.twitter.com/mCIEsN7oJJ

— olexander scherba🇺🇦 (@olex_scherba) March 19, 2022

A parallel could be drawn with an impromptu piano concert on the police barricades during the Euromaidan in February 2014, where a street piano had become a central location for protests. A group of artists, including singer and ethnomusicologist Ruslana, gathered to perform Western music, while the police on the other side attempted to drown the melodies with Russian pop – a confrontation between political alliances and musical genres that have come to signify the two sides of the conflict. It is an example of how music is used by social actors in specific local situations to erect boundaries, to maintain distinctions, and how terms such as authenticity or even ‘taste’ can be used to justify these boundaries (Stokes 2014).

The revolutionary status the Euromaidan piano came to embody was unforeseen by its creator Markiyan Maceh, who had gotten the idea from the street piano in Lviv. Throughout Euromaidan, the instrument welcomed many well-known and amateur musicians, and soon the idea of ‘the lonely pianist against a row of militia’ became a powerful symbol, proved so by Russian officials labelling it ‘piano extremism’. As a central symbol of the uprising, the piano was placed as close as possible to the police lines to make the police sympathise with the protesters, and, as a version of ‘external identity marketing’ (Brokaw 2001), to provide a striking image to the world’s media. Social performance is a practice in which meanings are generated, manipulated and even ironised (Stokes 2014, 12).

The Western city of Lviv, in Soviet times considered part of the ‘Soviet West’, became a key location where people fled to from the eastern region. The piano outside Lviv central station became a welcoming point for refugees, meeting point of musicians and an outlet for a range of emotions. Played every day, the piano witnessed Svyatoslav Vakarchuk perform his song ‘Hug me’ (‘The day will come when the war ends…’) through tears,a beautiful rendition of ‘What a Wonderful World’, and, perhaps the most powerful in my view, pianist Alex Pian’s performance alongside air raid sirens.

Hans Zimmer’s ‘Time’ took on a new meaning in this moment, described by Pian as his inner protest to ‘sirens, bombs, murders, and war’. Here, the violent conflict is literally inscribed within the life of music and recorded musical values, and provides an articulation of sonic dissonance in the social realm (O’Connell 2010). Three days later, Zimmer projected the video during his London concert as an act of solidarity. The sirens heard in this clip have become a daily soundtrack to urban life in Ukraine, and a key sound of the war, with field recordings going as far as calling it the true anthem of Russia.

An outdoor concert in Lviv on March 26th was cut short due to air raid sirens. The clip of the scene is astoundingly calm as the musicians and audience nod in acceptance and leave quietly to find cover before missile attacks. A month into the war, such activity had become part of everyday life, and outdoor concerts continued to take place on Kyiv’s Maidan Square, in Odesa and in Lviv. In addition to collective gatherings, more private and solo musical moments occured in homes and on the heavily bombed streets, as exemplified in this video of a musician playing ‘My Dear Mother’ by Maiboroda in Kharkiv.

In two instances of solo piano, we are privy to the different phases of the war. Before evacuating, a woman said goodbye to her bombed home in the town of Bila Tserkva, a moment that strikes a hopeful and resistant tone in comparison to this video of a soldier in Irpin almost a month later. From neighbouring Bucha, now synonymous with Russian war crimes, I have mapped only one video –this woman singing along to her music in the sun after spending 25 days in an underground shelter.

My analysis of the music collected in the mapping project is the first step towards understanding some of the ways in which music has appeared in–and is an integral part of–Ukrainian resistance. Each section of the map deserves individual attention, and there is potential for a more comprehensive project and documentary film in the growing numbers of footage (at 180 as of this posting).

I hope the project contributes to thought around music and conflict, specifically in Ukraine and Eastern Europe. While the map has been built from one person’s findings and so far only shows the moments filmed and shared publicly, the large number of entries already tells us much about the resistance, and the crucial role that media products can play in present-day military conflicts.

The focus of any applied ethnomusicology projects should be on Ukrainian war survivors for whom this research could prove beneficial. I also hope the map provides a sense of solidarity and a connection to Ukraine for those who have left and those who remain.

—

Merje Laiapea is a curator, artistic programmer and writer working across sound, music and film. She is completing her Master’s in Global Creative and Cultural Industries in the Music Department at SOAS, University of London. Within the broad realm of music and cultural identity, her research interests include the expressive power of the sound-image relationship, forms of frequency, and multimodal approaches to research itself. She assists with event production and community engagement at SOAS Concert Series and works as Submissions Advisor for the 2022 Film Africa festival. Merje also broadcasts the occasional radio show and DJ mix. To find out more about Merje’s motivation behind the project, click here to read an interview by the University of London.

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Deejaying her Listening: Learning through Life Stories of Human Rights Violations– Emmanuelle Sonntag and Bronwen Low

SO! Podcast #78: Ethical Storytelling in Podcasting–Laura Garbes, Alex Hanesworth, Babette Thomas, Jennifer Lynn Stoever

Reproducing Traces of War: Listening to Gas Shell Bombardment, 1918 – Brían Hanrahan

Twitchy Ears: A Document of Protest Sound at a Distance–Ben Tausig

Recent Comments